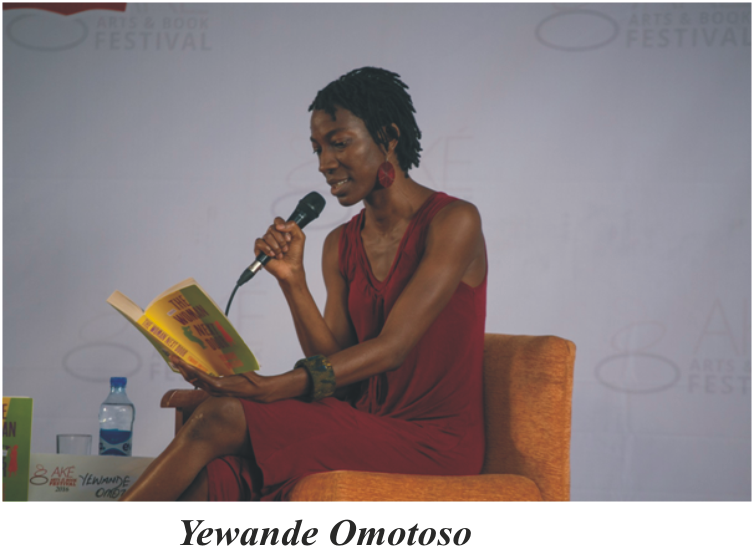

The Woman Next Door is Yewande Omotoso’s dark and comical second novel published in 2016 by Random House, South Africa and by Farafina in Nigeria. The story unfolds in what appears to be the first decade of the 21st century against a backdrop of a South Africa in the throes of being re-imagined though this contemporary framework vies for dominance with the novel’s historical context. History is the crucible in which its characters have been forged and here it spans a vast geography: imperial Britain, its colonies, the Bahamas and Nigeria post-independence, and crucially, South Africa pre-1994, under Apartheid. South Africa in the early 20th century, a time of slavery, unexpectedly intersecting with the main story, sheds ironic light on the relational dynamics between the octogenarian women who drive the narrative. They are:

‘Hortensia (James), black and small-boned, Marion (Agostino), white, large. Marion’s husband dead, Hortensia’s not yet. Marion and her brood of four, Hortensia with no children.’

‘The

wall is the thing which separates them, but it is also their means of

communication’ .

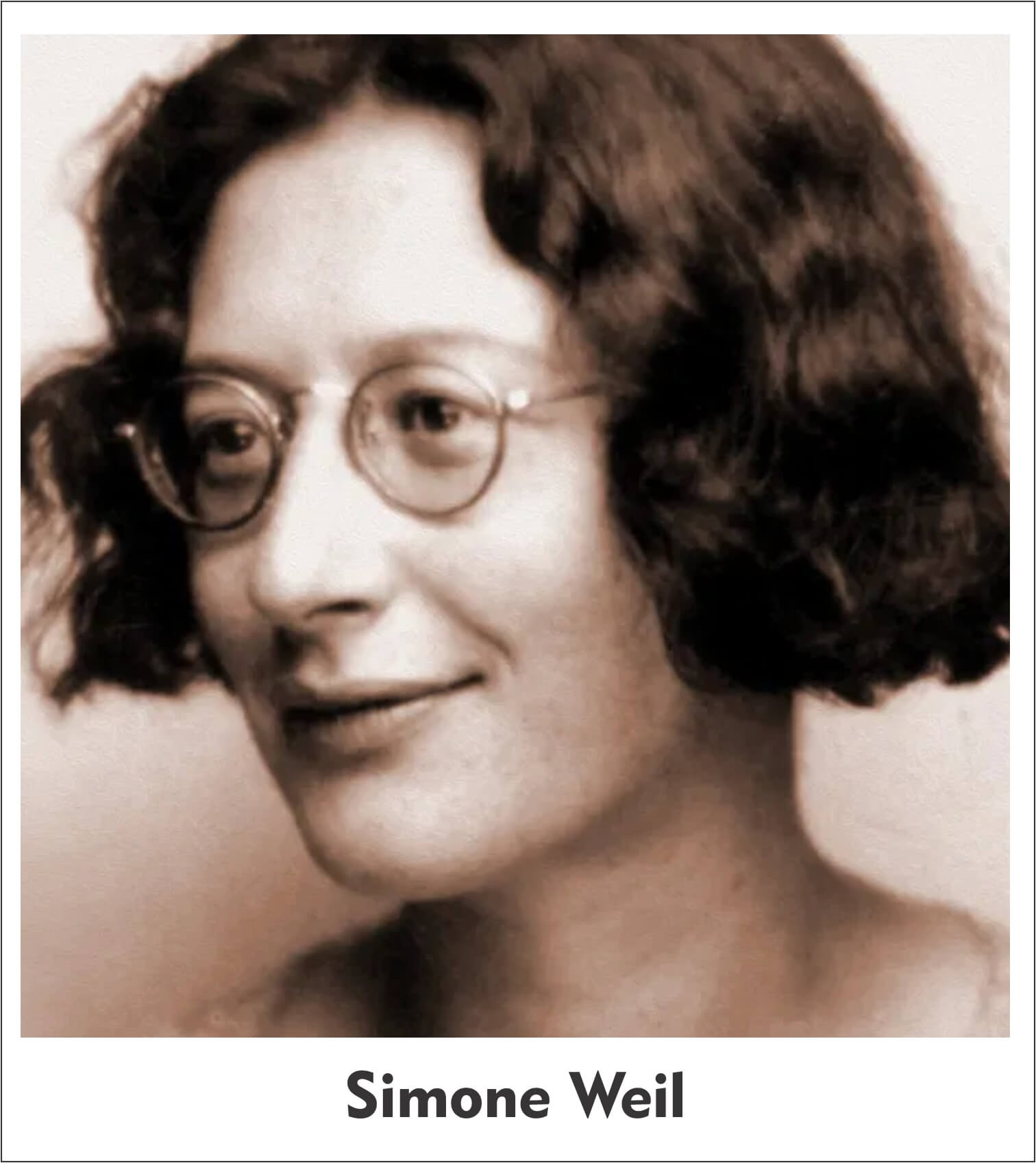

This abridged aphorism from Christian thinker and activist, Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace, prefaces The Woman Next Door, while the full aphorism, (not cited in Omotoso’s novel), foreshadows its mystical content and provides the map for interactions between the two antagonists living next door to each other in the expensive, historic Constantia estate known as Katterijn.

Side by side, moving from Hortensia to Marion, and back again, Omotoso relays their biographies, alternating perspectives, though finger-snapping Hortensia, comically imperious, even more entitled than racist Marion, takes up far more room. To each woman, next door houses the nightmare ‘other’. ‘Their rivalry was infamous enough for (the women on the Katterijn residents committee) to hang back and watch the show. It was known that the two women shared hedge and hatred and pruned both with a vim that belied their ages’.

Hortensia, fabric

design; Marion, architecture. The elderly women can boast of glittering,

competitive careers but all of that seems far behind them now as we share the lens

of the narrator. Speaking with a wisdom and calm, Omotoso presents her two

souls whose bitching and brinkmanship is

rivalled only by their warring against the world around them: domestic staff,

health caregivers, no-one is safe, particularly from childless Hortensia growling

under the weight of ‘memories (like) balls

of fire sitting in the centre of each earlobe’. Growling, she likes ‘to make people uncomfortable’ , likes

to frighten them. One time, after her customary halting climb to the small

height of the Koppie, her ‘prayer mountain’, we are rewarded with a

picture of insanity as Hortensia vents her rage on the trees that populate it.

We are even more alarmed to learn that the aim of all this yelling at trees, (thankfully

‘mute’ not ‘snivelling’ like human beings ) is to purge the hate of her ‘spitting’ self and settle into her colder,

normal‘pissed off self’.

Hortensia, fabric

design; Marion, architecture. The elderly women can boast of glittering,

competitive careers but all of that seems far behind them now as we share the lens

of the narrator. Speaking with a wisdom and calm, Omotoso presents her two

souls whose bitching and brinkmanship is

rivalled only by their warring against the world around them: domestic staff,

health caregivers, no-one is safe, particularly from childless Hortensia growling

under the weight of ‘memories (like) balls

of fire sitting in the centre of each earlobe’. Growling, she likes ‘to make people uncomfortable’ , likes

to frighten them. One time, after her customary halting climb to the small

height of the Koppie, her ‘prayer mountain’, we are rewarded with a

picture of insanity as Hortensia vents her rage on the trees that populate it.

We are even more alarmed to learn that the aim of all this yelling at trees, (thankfully

‘mute’ not ‘snivelling’ like human beings ) is to purge the hate of her ‘spitting’ self and settle into her colder,

normal‘pissed off self’.

And Marion? Since its inauguration in 1994 the disruptive policies of the ruling national party have frustrated Marion. ANC policies have disrupted the status quo. As if that were not bad enough, her own children (who grew up with terrifying speed), seemed to be on their side, persistently asking embarrassingly logical questions - ‘(Does) a black beach have black sand?’ - persistently challenging the way things were arranged in South Africa and her own comfort with that arrangement. Beside herself with frustration, Marion spent a lifetime waging against her now late husband using the ‘the love of their children (whom Max loved unconditionally) as artillery... because it is much easier to fight your husband’ than a remote, sprawling entity called the ANC.

I marvel at Omotoso’s literary capacities: her

ability to channel the women’s voices as she, omniscient narrator, tells their

stories; her ability to carve lean and muscular sentences out of such descriptive

wealth. I took time to enjoy her gleaming prose, studded with images, metaphors

and thought patterns with which progressively –masterfully – she reveals the truth:

that the wall separating these women is far more fragile, far lighter in weight

than the psychology and social alienation they share and which create the

channels for their communication. There is a memorable image towards the end of

the book, during a time of detente. The women, sitting in Hortensia’s garden,

look up to see that the birds whose blue plumage they have just sighted have ‘taken off, two specks in an empty sky’. But I saw no birds, what I saw beneath the

canvas of sky were two peas in an empty pod, at once dark and comical, the other, a lighter

shade of green; two old women sitting on a bench, sharing their isolation from

the world.

I marvel at Omotoso’s literary capacities: her

ability to channel the women’s voices as she, omniscient narrator, tells their

stories; her ability to carve lean and muscular sentences out of such descriptive

wealth. I took time to enjoy her gleaming prose, studded with images, metaphors

and thought patterns with which progressively –masterfully – she reveals the truth:

that the wall separating these women is far more fragile, far lighter in weight

than the psychology and social alienation they share and which create the

channels for their communication. There is a memorable image towards the end of

the book, during a time of detente. The women, sitting in Hortensia’s garden,

look up to see that the birds whose blue plumage they have just sighted have ‘taken off, two specks in an empty sky’. But I saw no birds, what I saw beneath the

canvas of sky were two peas in an empty pod, at once dark and comical, the other, a lighter

shade of green; two old women sitting on a bench, sharing their isolation from

the world.

Tracing the arc of this story, biblical psalms come to mind, the kind that begin as dirges, or as a set of strident protestations calling for the punishment of enemies (such as time, poverty, sickness, other people, always other people), but end on softer notes: the gentle stirrings of a revival of faith in living. As it progresses, the book looks increasingly like the stage Omotoso has mounted to display the trinity of forces Simone Weil explores in Gravity and Grace.

The first element of this trinity is the gravitational pull in the human soul and body towards decay, disorder and degeneration and indeed the first sentence in the book details the drawn-out dying of Hortensia's husband, Peter James, from Alzheimer’s – a degenerative disease. The sub-text of virtually every scene in this fictional biography, furnishes the second element: the corrosive power on human personality of this gravitational pull: We will let others down; we will let ourselves down even when we aspire to better ways of being so don’t be surprised to find in this book fervent attempts at reconciliation and desperate attempts to confess, initiated only to be aborted. Starting with fervour, the characters stop with fear, back down. The third and final element of the trinity is providence or, in the Christian doctrine to which Simone Weil subscribes, Grace, the supernatural intervention of God breaking through the gravity which imprisons us.

Grace alone can stop us fighting, spitting poison; can free us from a prideful obsession with ‘things’, from our selfishness and compulsive lying. Grace will wash away our masks of hypocrisy and release us from the tyrannical need to impose our own perceptions of order and beauty, on the world around us. Throughout the book you will find the human instinct for order distorted in both women obsessing over ‘lines’, over the symmetry of furniture (and human facial) arrangements, ‘fretting for days’ about dirt and stains, frantically searching for heaven (a safe haven) in materiality. Counterforce to Gravity, Grace alone can liberate our capacities for human justice, for respect and fellowship, (even love), for patience and for peace, for shalom - and as I read I heard sounds of a hymn not to the human condition as it is but to the possibilities we carry within our humanity.

Hortensia’s fall by a trailer is memorably comical, but this is the only time in the novel that Grace bulldozes its way in. More often, it surprises the women with its gentle light: the unexpected good looks of the elderly doctor, Gordon Mama, and his delicate handling of Hortensia which displays a saintly patience and a sense of humour reminiscent of the best Christian priests. Cook Bassey’s preparation and offering of a sumptuous breakfast for the doctor and the elderly women, this, this is the breaking of bread. In the ‘mean cup of hot chocolate’ from Hortensia’s hand to Marion’s grandchild, I see the drink offering of the Eucharistic feast. It is interesting that a blind woman young enough to be her daughter should be the one to reveal to the celebrity fabric designer, the beauty that can reside in every human heart including her own. This is the wisdom of the Bible.

Taken at face value, The Woman Next Door is a thought provoking, entertaining and immensely readable fictional biography. As an allegory of race relations in contemporary South Africa, however, Yewande Omotoso has written an outstanding book. After the nightmare of Apartheid, Truth and Reconciliation Commissions are a necessary political prescription for a nation on a path to healing but these commissions are imposed, a product of government agency, not individual will. What Omotoso points us to in her book is the personal, introspective road to the Rainbow Nation. Here, the path to a new creation is paved with seeds of desire for reconciliation in each human heart; seeds of desire that will bud and blossom when they are cultivated by all kinds of movements of God’s Grace through the human condition. Click Here to get a copy