Teju Cole wrote the now famous Open City. Like him, you too are a great scholar. It’s hard to miss references to literary works throughout your text; evocations contextualise your thoughts or texture and colour your frames. I agree with Teju though that your writing is ‘free of the starchiness of undigested scholarship’. I also agree with his foreword which is pure praise.

How did you feel when you first read it? Any stand out parts? Were there any comments he made that took you aback?

My gratitude to him when I read it was immense, and continues to be. For the foreword, in the first place. But also the extent to which he has affirmed our kinship. I imagine our conversation as ongoing.

To what extent if any was A Stranger’s Pose inspired by Open City?

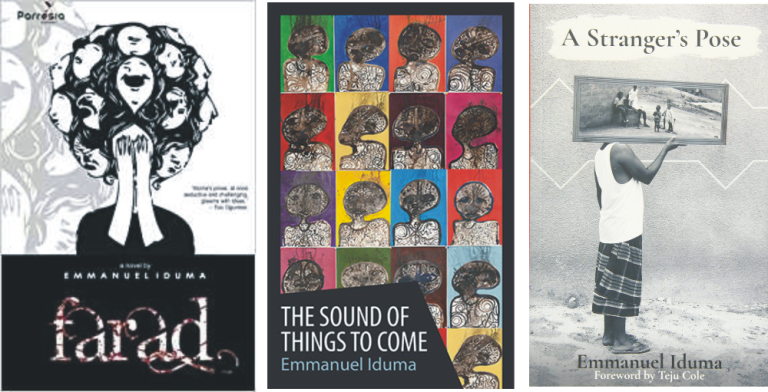

There

were other books of his, in fact, that inspired me to

finish mine. One was the collection of essays, Known and Strange Things,

and the book in which he paired texts and images, Blind Spot. In both

cases, it was the commitment to clarity, but also to opacity-the resolved and

the irresolvable-that seemed to me most admirable.

Teju Cole’s Julian is fictional. You are the central character of A Stranger’s Pose which is your memoir. But both central characters are travellers. Yours is a motorised road-trip across Africa, while Julian is a flâneur who walks New York city on foot.

Share the story of your work with Invisible Borders with us. How did it all begin?

I had just

completed my studies at the Nigerian Law School. I needed a vocation that could

validate my decision not to practice law. At the time I’d followed the work of Invisible

Borders for two years. And so, after an email inquiry to Emeka Okereke,

I was asked to share my writing samples. What followed was an invitation to

participate in the third edition of the road trip. Things really took off from

there.

Share one or two major high points from your road trips with Invisible Borders and one or two of the most frustrating or harrowing challenges which you and your friends experienced.

I did a

fair amount of documentation of my travels with the organization, and for the

sake of space I’ll like to simply point readers to the blog posts on the Invisible

Borders website, from my travels in 2012, 2014, and 2016. It might be

the best way to ensure that my impressions of those weeks on the road are

relayed with the same immediacy of feeling, perhaps cogency, as when they were

experienced.

I am a

subscriber to your blog A Sum of Encounters which features

profile essays on Nigerian artists based in Nigeria and the United States.

Thank you for sharing the blog with me. The posts are beautifully written and

rich in information about each artist. I particularly enjoyed the feature on

Abraham Oghobase. You were awarded a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation

Arts Writers Grant to do this.

Tell us about this grant, how it works and about the envisaged outcomes of the collaboration.

It’s a well-known grant in the art writing community-I first head about it from my teachers at the School of Visual Arts who had won it. As such it was a real honor to be offered it. I was given the freedom to develop the blog as I’d proposed: my idea was to write narrative essays on the life and work of Nigerian artists, based in Nigeria or the United States, informed by time spent at their studios or houses, or after lengthy consideration of their bodies of work. My goal was to do this within the course of a year.

What I’m

most proud of, after eight of those essays, is how the project have taught me

to practice narrative as criticism. To consider experience as the entry point

to reflection on art, and as a model for art criticism as a genre of

literature.

I’d like to keep going with the project, in some way, over the next year or two. I’m now working on two additional essays in this series, and then I’ll consider what next steps to take. I’m propelled by the notion that the artist is in the world, working out what it means to feel and see.

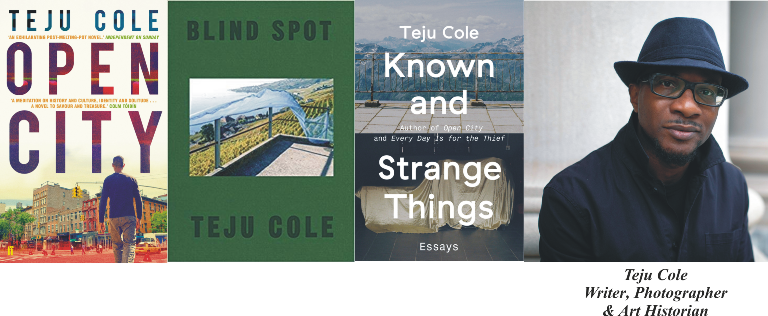

Apart from A Sum of Encounters, you’ve contributed essays to prestigious magazines, journals such as Chimurenga, Guernica, ARTNews, British Journal of Photography and to artists’s books by notable international artists including Nigeria’s Victor Ehikhamenor.

If you were to stop and reflect, which hat do you believe you wear more comfortably: your art writer’s hat or your hat as a travel writer?

I’m inclined to work with a commitment to range, rather than with hierarchies. When I started writing about art about seven years ago, I didn’t think I was an art writer, only a writer interested in art. It helped that I’d completed a novel before joining Invisible Borders—I was, as such, a writer being immersed in visual art, learning how to see the world. I think, however, that having studied Art Criticism, my writing became focused on art writing. My goal for my writing, as we speak, is to free myself from any prescriptive tendencies I might have acquired. To work as a writer writ large, and learn from each project—essay, short story, nonfiction book, novel—what it requires. Some might take years to complete; I must learn patience.

It’s great to learn that Nana Oforiatta Ayim is curating Ghana’s inaugural Pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year, 2019. But we beat Ghana to it. In 2017, you went to the 2017 Venice Biennale with Qudus Onikeku, the talented dancer (trained as a circus performer!); Victor Ehikhamenor and Peju Alatise, both international, award-winning visual artists. Your quartet hosted Nigeria’s first ever Pavilion. You served as associate curator and also as the project scribe didn’t you?

Our country is blessed with talented artists. Why did it take so

long for Nigeria to host a  Pavilion at the world’s foremost Biennale?

Pavilion at the world’s foremost Biennale?

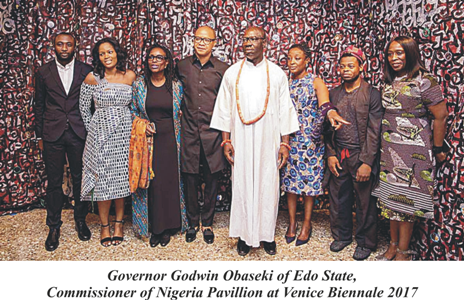

The curator of the exhibition was Adenrele Sonariwo, and I was associate curator-so it wasn’t a quartet, per se. The commissioner of the pavilion was Godwin Obaseki, the Edo State governor. There were other actors, as well: a Steering Committee, and a team of project managers and communication experts. Several factors, I think. Notably that it takes a lot of resources to pull off an exhibition of that magnitude, and the easiest way to get it done is for it to be funded by government. And we know the story of political will when it comes to funding cultural production in Nigeria.

What were the selection or nomination criteria for this first set of exhibitors?

The artists that presented work in the Biennale are at the height of their powers, making what we can describe as mid-career work. It was important to us to work with artists who understood the value of the exhibition, and who saw their contribution as part of a larger conversation-that of the nature of time in relation to Nigeria, and how artistic output could be seen as a marker of such time.

The challenges you faced preparing to go to Venice to represent your country. Share some of them with us.

The main challenge was funding, which meant that we spent a shorter amount of time planning the exhibition. It’s remarkable to think of what we achieved in such short time.

What was the reception like to the various exhibitions your group staged in the Pavilion? Tell us for example about the kinds of audiences you had each day.

The exhibition was received well. One standout moment, for me, was when Qudus Onikeku performed a day after the opening. It was in the first gallery of the space we used and, although we hadn’t formally put out word of the performance, the space was crowded. It was an indication of how quickly word had spread about our pavilion, and the measure of solidarity being expressed with us.

Saraba, the online literary magazine with its headquarters here in Lagos, was founded by you and Dami Ajayi, the well-known psychiatrist and poet. In the ten years since inception, it has garnered a worldwide following and deserved renown.

Talk to us about Saraba’s wonderful work promoting emerging African

writers: how do you go about promoting them?

Talk to us about Saraba’s wonderful work promoting emerging African

writers: how do you go about promoting them?

To date, we have published over 300 writers, whether in our magazine issues, chapbooks, or special issues. Our main motivation is to give writers at the outset of their careers opportunity to have their work featured in a prominent literary magazine. The promotion, as a result, is really this opportunity—the exposure to editorial rigour, for instance. And, each issue is carefully produced, and distributed to several thousand supporters.

Our first print issue in 2017. And, following from the Manuscript Project we organized, the publication of T J Benson’s We Won’t Fade into Darkness, one of the shortlisted fiction manuscripts.

And what have been the greatest challenges to your growth?

The magazine has largely been distributed free of charge, digitally, for 10 years. We’ve been seeking opportunities to grow the magazine financially. I wouldn’t call it a challenge to growth, but a matter we intend to resolve.

Finally, tell us about your life as an expatriate (or are you an exile?) in the US. When did you leave Nigeria?

And if it’s not too personal, why did you leave?

I left Nigeria in 2013, to study for a masters degree. Exile is not a word I’ll use, since I maintain ties to Nigeria. I return as frequently as I can. My family is here. I enjoy being here.

I’m working on my next book.

This Interview is published in Guardian Nigeria: https://guardian.ng/art/for-iduma-author-of-a-strangers-pose-exile-is-not-a-word/

I am drawn to people of mixed-cultural descent and of mixed-race heritage. I'm also drawn to ...

David Aguilar, born in Andorra, is an inspiring figure known for his resilience and crea ...