International Publishers Association Seminar

Publishing for Sustainable Development:The Role of Publishers in Africa

Lagos 9 May 2018

Hosted at Eko Hotels & Suites, Lagos, Nigeria

REVIEW

On May 2

this year, the Facebook group, Book Publishing in Africa, shared a press release with the community. The news was from the Nigerian Publishers Association (NPA), announcing

the first ever summit of the International Publishers Association (IPA) to take

place in Africa. The first ever to be held on this continent in all of its 122

years, representing the interests of publishers and the book industry

internationally; promoting and defending copyright, and the freedom to publish

as a fundamental aspect of the human right to freedom of expression.

On May 2

this year, the Facebook group, Book Publishing in Africa, shared a press release with the community. The news was from the Nigerian Publishers Association (NPA), announcing

the first ever summit of the International Publishers Association (IPA) to take

place in Africa. The first ever to be held on this continent in all of its 122

years, representing the interests of publishers and the book industry

internationally; promoting and defending copyright, and the freedom to publish

as a fundamental aspect of the human right to freedom of expression.

The author of the release, NPA President, Gbadega Adedapo, provided the

background to the seminar, listing its objectives, striking a justifiably

triumphant note since the seminar, slated for Wednesday 9 May 2018, would be

hosted by the NPA in Lagos in the impressive setting of the Eko Hotel &

Suites. A first and an honour indeed. I could hear the drum rolls before each

of the names the procession of the publishing luminaries from across the globe

who would be attending the event - in person: the IPA President himself, Dr.

Michiel Kolman; Brian Wafawarowa, President of the Publishers Association of

South Africa; Elliot Agyare, President of the Ghana Book Publishers

Association; Kristen Einarsson, Managing Director, Norwegian Publishers

Association and the Chairman of the IPA's Freedom to Publish Committee; Jose

Borghino, IPA Secretary-General; Bodour Al Qasimi, President, Emirates

Publishers Association and Chair, Sharjah World Book Capital 2019. The heaviest

weights in publishing were coming to our city, this our Lagos, with a view to

identifying challenges and opportunities for the industry of publishing in

Africa and to make concrete proposals for its advancement. The title of the

seminar: Publishing for Sustainable Development: The Role of Publishers in

Africa.

attending the event - in person: the IPA President himself, Dr.

Michiel Kolman; Brian Wafawarowa, President of the Publishers Association of

South Africa; Elliot Agyare, President of the Ghana Book Publishers

Association; Kristen Einarsson, Managing Director, Norwegian Publishers

Association and the Chairman of the IPA's Freedom to Publish Committee; Jose

Borghino, IPA Secretary-General; Bodour Al Qasimi, President, Emirates

Publishers Association and Chair, Sharjah World Book Capital 2019. The heaviest

weights in publishing were coming to our city, this our Lagos, with a view to

identifying challenges and opportunities for the industry of publishing in

Africa and to make concrete proposals for its advancement. The title of the

seminar: Publishing for Sustainable Development: The Role of Publishers in

Africa.

But scepticism about tangible outcomes from the forthcoming IPA/NPA seminar could not diminish astonishment about one thing: the number of major international conferences and meetings on the African book industries that have taken place on African soil in the space of just six months. First the WIPO conference in Yaounde in November 2017, for which an action plan was recently circulated; then the Global Book Allliance/ADEA/USAID-sponsored conference in January, for which a report has been published. The third is this IPA seminar which will no doubt come out with its own action plan in due course.

Though it appears to have erupted overnight, I am far less surprised about the global book industry's excitement about Africa. Why? I am a literary journalist and a joyful witness to what in the past fifteen years or so have been an exploding literary production by African writers at home and in the diasporas. The results have been amazing: Africans are on awards long lists, on awards short lists, or winning the awards outright. And prestigious awards such as the Etisalat Prize for Literature (now 9 mobile) and Lumina Foundation's Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature, have been instituted to recognise our gifted ones right here on the continent - at home. Nowadays, our writers are making headlines regularly in international book news. Teju Cole (Nigeria); Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya); Yewande Omotoso (Nigeria/South Africa); Tomi Adeyemi (Nigeria/USA); Biyi Bandele (Nigeria); Noo Saro-Wiwa (Nigeria); Lesley Nneka Arimah (Nigeria); Mona Eltahawy (Egypt); Sisonke Msimang (South Africa); Yvonne Owuor (Kenya); Helon Habila (Nigeria); Abubakar Adam Ibrahim (Nigeria); Elnathan John (Nigeria; Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria); Ayobami Adebayo (Nigeria). Minna Salami (Nigeria); Imbolo Mbue (Cameroon); Yaa Gyasi (Ghana); Fiston Mwanza Mujila (DRC). So many more emerging, standing out, globally. And look at the number of Nigerians on this list...

Dare I use the word 'sexy'? Because overnight it seems that is exactly what African literature has become! Extending its meaning to include bloggers, in a revival we have never seen the likes of before due to the new abundance of media platforms channelling African voices into a world hungry to consume any kind of 'book' form; a world hungry also to consume the glamour that seems so much a part of the 'book deal'. Right now I would argue that literature is Africa's sexiest export. Might this phenomenon be what IPA President, Michiel Kolman, was evoking in his Welcome Address when he referred to: "...the voice of Africa"? Repeating that "This voice is the voice the IPA wants to hear today".

Why else would the Nigerian Publishers Association choose as its keynote speaker, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the photogenic literary icon with extremely high global visibility? Why not a distinguished practitioner of the African book trade? The NPA also selected Ayobami Adebayo, a beautiful young woman of barely thirty years who has in the past two years won and been short-listed for a plethora of international prizes (including the prestigious Bailey's Prize for Women's Fiction). Adebayo was selected as a panel moderator. According to Mohammed Radi, Vice-Chair of the African Publishers Network, West Africa has been identified as the region in Africa with the strongest reading culture. The IPA can only admit African members for countries who have an active national publishing and/or book trade association, and in many African countries they still not exist, or are dormant. Because of this the IPA is dominated by western presses. Those at the helm of these presses must be asking how best to maximise the immense opportunity which West Africa represents - today - as an emerging book market. In 2014 Rivers State Government hosted the UNESCO World Book Capital project in Port Harcourt. Lagos State Government is pushing a Lagos Reads campaign in libraries in a bid to augment the budding interest of Lagosians in reading. The question for the NPA now must be how to meet demand at home and abroad with supply from a well-structured, functional book trade. At this juncture, let me clarify the mission of the NPA which is 'to create an enabling environment and secure favourable trade terms both within Nigeria and overseas.' (NPA Press Release, Wednesday, 2 May 2018)

THE SEMINAR

So these are exciting times for publishing in Africa and I attended the IPA/NPA summit with a hopeful heart. I looked forward to strong government presence, practical recommendations, and tangible solutions in action plans to be published subsequent to the seminar and made widely available.

Well organized and convened in the setting of Eko Hotel & Suites whose

outdoor layout leverages the beauty of the tropics, the seminar was full to

bursting. As expected in a heavily-sponsored event*, equipment is prone to

malfunction from time to time: yet air-conditioners, public address system, and

simultaneous translation equipment, worked flawlessly. Audience contribution to

panel discussions was digitised on social media via #IPALagos18. The luminaries

from across the globe I earlier mentioned, and important stakeholders in the

local book chain, were there in force but, sadly, the Nigerian Government was

not. Only one major player, Afam Ezekude, Director General of the Nigeria

Copyright Commission (NCC) was present as far as I know to discuss and

debate with other stakeholders. They stayed on throughout the day, remaining in

a convivial mood, well-fed (the food was very good) and stimulated by the

advocacy and campaigning to change the direction of publishing, nodding their

heads along with the lamentations, and with the recommendations from speeches

moderated efficiently on the stage.

Well organized and convened in the setting of Eko Hotel & Suites whose

outdoor layout leverages the beauty of the tropics, the seminar was full to

bursting. As expected in a heavily-sponsored event*, equipment is prone to

malfunction from time to time: yet air-conditioners, public address system, and

simultaneous translation equipment, worked flawlessly. Audience contribution to

panel discussions was digitised on social media via #IPALagos18. The luminaries

from across the globe I earlier mentioned, and important stakeholders in the

local book chain, were there in force but, sadly, the Nigerian Government was

not. Only one major player, Afam Ezekude, Director General of the Nigeria

Copyright Commission (NCC) was present as far as I know to discuss and

debate with other stakeholders. They stayed on throughout the day, remaining in

a convivial mood, well-fed (the food was very good) and stimulated by the

advocacy and campaigning to change the direction of publishing, nodding their

heads along with the lamentations, and with the recommendations from speeches

moderated efficiently on the stage.

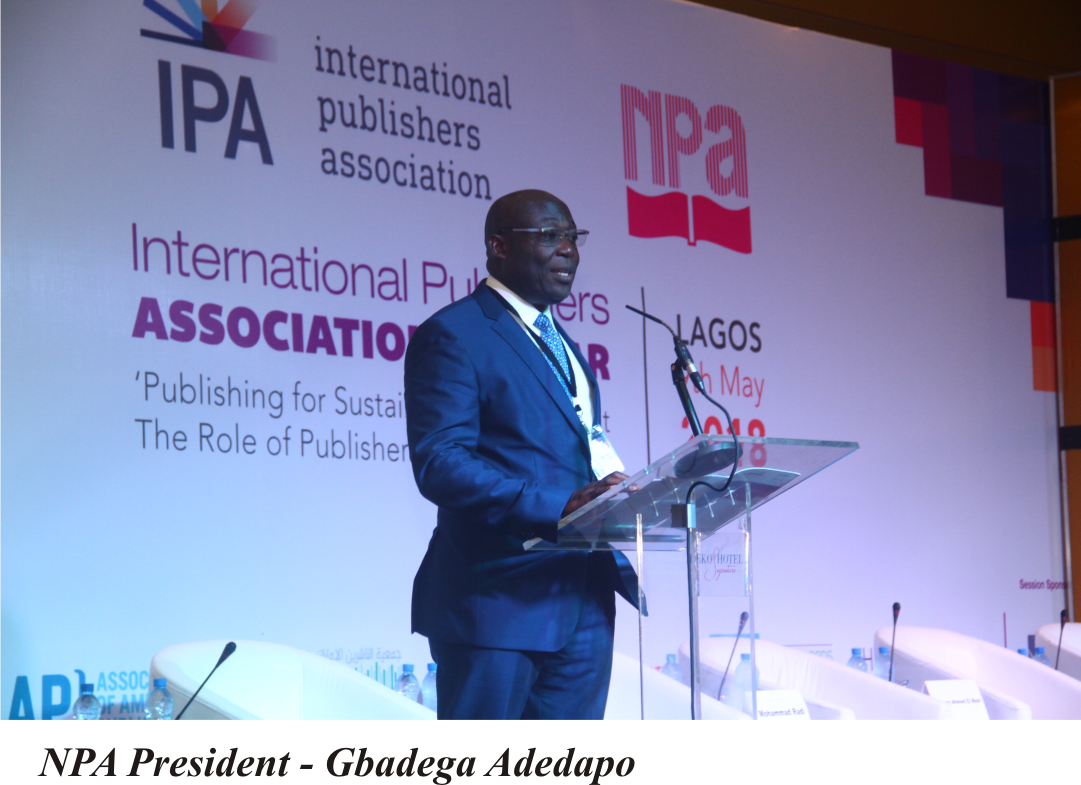

In his own Welcome Address, NPA President, Gbadega Adedapo decried

rampant piracy threatening the very core of publishing; he stressed the need to

prove to Government that as an employer of labour contributing heavily to GDP,

the publishing industry is extremely important to development and made a big,

bold and mystifying statement that has since been posted and discussed by his

publishing peers on Facebook. To paraphrase his words: "rough estimates

of the African publishing market show its value as being more than US$1 billion

and the market is showing cumulative annual growth of 6%." The query

of many of his colleagues centres on Adedapo's sources: just which book

industry statistics, or other data, are these figures based on.

In his own Welcome Address, NPA President, Gbadega Adedapo decried

rampant piracy threatening the very core of publishing; he stressed the need to

prove to Government that as an employer of labour contributing heavily to GDP,

the publishing industry is extremely important to development and made a big,

bold and mystifying statement that has since been posted and discussed by his

publishing peers on Facebook. To paraphrase his words: "rough estimates

of the African publishing market show its value as being more than US$1 billion

and the market is showing cumulative annual growth of 6%." The query

of many of his colleagues centres on Adedapo's sources: just which book

industry statistics, or other data, are these figures based on.

Finally, Gbadega Adedapo promised a 'Lagos Action Plan 2018' , that is the blueprint to emerge from the seminar which would 'revolutionise publishing in Africa' . What a promise!

Literary icon, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, was - in the end - not there to

give the keynote speech, but six power panels were present as scheduled to

discuss a variety of key issues:

Panel Discussion 1: Publishing in the 21st century: The Socio-Economic Contribution of the Publishing Industry in Africa.

This discussion was defined by bitter complaints from the delegates about sub-par book production quality as well as quantity, lack of distribution networks, and the apathy of government to intervene. Sellami Ahmed El Meki, President of the Mauritanian Publishers Association, was particularly vocal about the inability of publishing to impact his nation's socio-economic growth due to these deficits. With recognition as a serious industry, he argued, publishing would be in a position to attract great investment, but from "our own income rather than from external sources".

Elliot Agyare, President of Ghana's Book Publishers Association made the stand-out and lofty case for publishers to take themselves far more seriously as "gate-keepers of society", referencing the biblical concept of eminent men meeting at the gates of the city to discuss affairs of state. The gate-keeping role of publishers in African society needs, he argued, to be conceptualised and birthed.

Other (one could say somewhat deja vu) contributions came from, for example Mohammed Radi, Vice-Chair, African Publishers Network who advocated learning from the industry models of more advanced countries by joining international associations and establishing relationships with editors and publishers; the huge commercial value of book fairs; and the necessity for both economic and literary approaches to marketing books.

The key element of the 'socio-economic' discussion was for me its

emphasis on government's need to measure the outputs of the creative industries

and the urgency for data gathering and book sector statistics in Africa - hard

data - without which our reports are mere anecdotes. An audience member who

introduced the principle of output measurement spoke passionately: if African

governments won't undertake data gathering, he argued, then publishers

associations must. He finished by proposing that a call for systematic data and

information collection about the publishing industry of each African country be

recorded as a concrete and urgent action in the blue print, the Lagos Action

Plan 2018 , that will emerge from the seminar. In support of this line of

reasoning the moderator, Samuel Kolawole, MD, University Press Ibadan ,

closed the panel with the recognition that the total (and undermining)

inability of publishers on the panel to articulate how their outputs impact

specific Sustainable Development Goals of the 17 outlined by the UN, was a

direct result of the lack of verifiable and quantifiable publishing data to

hand.

The key element of the 'socio-economic' discussion was for me its

emphasis on government's need to measure the outputs of the creative industries

and the urgency for data gathering and book sector statistics in Africa - hard

data - without which our reports are mere anecdotes. An audience member who

introduced the principle of output measurement spoke passionately: if African

governments won't undertake data gathering, he argued, then publishers

associations must. He finished by proposing that a call for systematic data and

information collection about the publishing industry of each African country be

recorded as a concrete and urgent action in the blue print, the Lagos Action

Plan 2018 , that will emerge from the seminar. In support of this line of

reasoning the moderator, Samuel Kolawole, MD, University Press Ibadan ,

closed the panel with the recognition that the total (and undermining)

inability of publishers on the panel to articulate how their outputs impact

specific Sustainable Development Goals of the 17 outlined by the UN, was a

direct result of the lack of verifiable and quantifiable publishing data to

hand.

And while the lack of formal distribution networks was mentioned repeatedly, no-one in this socio-economic panel spoke of poor road networks and the high cost of transportation and not until the Panel 3 discussion 'Bringing the Voice of African Writers to the World', would the subject be addressed by author, publisher and Ake festival convener, Lola Shoneyin, of unreliable postal system e.g. NIPOST in Nigeria.

Another omission was the golden opportunity for the African book trade represented by increasingly secure and reliable online payment systems in Nigeria. The country might normally be associated with cyber crime, but things are changing in the realm of electronic payments and this hope for the Nigerian book industry was not presented: perhaps because it is not yet universally understood.

My final point: on a socio-economic impact panel, why was there no mention of the taxation of books in some countries by way of debilitating tariffs of VAT and/or import duties, with VAT charges ranging from 14%-18%?

Panel Discussion 2: Strengthening Educational Publishing in Africa.

Stand-out speakers on this panel were Otunba Olayinka Lawal-Solarin of Litramed; Lily Nyariki, Bookshop Manager at Moi University in Kenya and an official of Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) and the moderator, Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi, Chairman of Tanus Communications.

Otunba Olayinka Lawal-Solarin spoke passionately about banks being unwilling to fund the text book publishing sector because it is not perceived as a lucrative investment. He spoke of non-existent marketing mechanisms; of the corruption of government officials blighting the marketing of books to government; of the book policy of 1 book: 5 pupils which works out in reality as 1 book: 15 children. He lamented the impossibility of educating Nigerian children in the face of stifling book to child ratios. Lily Nyariki spoke of shortage of books across the whole of Africa, agreeing with Otunba Lawal-Solarin about the pupil to book ratios in Africa gravely compromising the quality of education of the African child.

Since Government is clearly not in a position to fund its own policy of 1 book: 5 children, Otunba Lawal-Solarin proposed that government transfer the cost of book provision as per the existing policy to the parents via a revised policy. The new policy would mandate parents to buy five core text books for their children resulting in a market for textbooks and enabling publishing to thrive. He had barely finished speaking when an audience member jumped out of his seat to make a terse rejoinder: "Parents cannot and should not bear the cost of the five books. That is for government to do."

The audience member was no doubt thinking about the increasing number of African governments now heavily taxing books and in this way taxing knowledge through debilitating tariffs, VAT and others with a devastating effect not only on the cost of educational book supplies and reading materials but on the cost of books generally. Retail prices are now reaching astronomical levels in some countries.

Lily Nyariki, (the only bookseller panellist, I believe), stated the obvious: without a reading culture, publishing is at risk of dying. It needed to be said in the case she was making for increased recognition for booksellers who are crucial to the educational system and a key link in the publishing chain. Publicists and literary journalists like myself are also an under-represented but important cadre of the book chain, so I was happy to hear Ms. Nyariki extend her argument to us, by making the case for strengthening each link in the book chain.

In a bid to differentiate the challenges faced by educational publishers from

those faced by publishers of  general and trade books, fiction and other

creative writing, Ms. Nyariki further spelled out the key elements of

educational publishing: developing, producing, distributing, disseminating and

use. As part of her slide presentation, she spoke of unethical practices (did I

see poor credit record of some booksellers one one of the slides?). The slide

show traced the trajectory of books from source to end result covering the

advantages and disadvantages of direct selling which she explained is prevalent

in Africa. Nyariki's presentation was rich in specifics. She highlighted book

distribution styles currently found on the continent, which are largely unclear

but include monopolies and the free market model. Clearly aware of the all

talk no action reputation of these conferences, she closed her speech with

an offer to share ADEA's action plan that emerged from its own Abidjan

conference, held in January this year, with stakeholders present at the IPA/NPA

seminar and expressed the openness of ADEA to for relevant collaborations.

general and trade books, fiction and other

creative writing, Ms. Nyariki further spelled out the key elements of

educational publishing: developing, producing, distributing, disseminating and

use. As part of her slide presentation, she spoke of unethical practices (did I

see poor credit record of some booksellers one one of the slides?). The slide

show traced the trajectory of books from source to end result covering the

advantages and disadvantages of direct selling which she explained is prevalent

in Africa. Nyariki's presentation was rich in specifics. She highlighted book

distribution styles currently found on the continent, which are largely unclear

but include monopolies and the free market model. Clearly aware of the all

talk no action reputation of these conferences, she closed her speech with

an offer to share ADEA's action plan that emerged from its own Abidjan

conference, held in January this year, with stakeholders present at the IPA/NPA

seminar and expressed the openness of ADEA to for relevant collaborations.

The highlight of the discussion was moderator Yemi Ogunbiyi repeatedly advocating taking a leaf from the Nollywood book and extolling Nollywood's independence. "Nollywood doesn't need government support!" he declared. "It's in fact, the other way round: it's government that's looking to the film industry! Why can't the book industry follow the Nollywood model?"

No-one on the panel seemed in a position to respond - perhaps due to lack of information about the Nollywood model? - but Elliot Agyare, President of the Ghana Publishers Association, this time speaking from the audience, dismissed the Nollywood model as being a totally different scenario. "Government is in charge of education", he stated firmly, "it is in charge of the provision of books for schools, government is not in charge of funding entertainment".

Other issues were addressed, including the underrepresentation of women in educational publishing and the need for diversity in publishing; teacher training and improved teaching materials; and promotion of the reading culture. What no-one mentioned is the new threat by some African governments to introduce and implement a policy of just one officially sanctioned textbook per subject and grade, thus ending the current situation of a multiplicity of books from a variety of publishing houses, competing in an open market. Why was there silence about this danger?

Panel Discussion 3: Bringing the Voice of African Writers, Publishers and Content Creators to the World.

This was a colourful panel with Nigerian Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, co-founder of up and coming publisher, Cassava Republic, as moderator. Bakare-Yusuf, a petite woman with incredible energy, narrowed the focus of 'the world' to Africa, this part of the world. She did a wise thing: intra-African book trade, bounding with opportunities, is fraught with many logistical impediments to its success: among them getting books through customs, taxes and tariffs. Intra-African book trade is also dear to the heart of Lola Shoneyin, publisher and founder of Ouida Books and a panelist for the session. It must be seen, she declared, as a "huge opportunity", calling for analysis followed by specific and sustainable action toward significant revenue generation, action that will be driven by a coalition of serious actors on the continent.

But Akoss Ofori of Sub-Saharan Publishers and African Books Collective

was the first to speak. She began with her concern about the deterioration of

public library services, many of them without book acquisition funds, and

argued for every country's government to distribute books in good quantities to

libraries across their countries. Veteran Tanzanian publisher Walter Bgoya

of Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, and Chairman of African Books Collective

supported Ofori's position with a reference to the Norwegian government's

policy of buying 1,000 copies of every title published in the country to give

to its country's libraries. Regrettably neither of these two representatives of

ABC spoke about another related topic: the activities of overseas book donation

programmes, and their potential negative effects on the local book industries.

There are serious pitfalls as libraries across the African continent

increasingly rely on these book aid schemes in their hunger for books and to

fill their empty - at best scanty - shelves.

But Akoss Ofori of Sub-Saharan Publishers and African Books Collective

was the first to speak. She began with her concern about the deterioration of

public library services, many of them without book acquisition funds, and

argued for every country's government to distribute books in good quantities to

libraries across their countries. Veteran Tanzanian publisher Walter Bgoya

of Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, and Chairman of African Books Collective

supported Ofori's position with a reference to the Norwegian government's

policy of buying 1,000 copies of every title published in the country to give

to its country's libraries. Regrettably neither of these two representatives of

ABC spoke about another related topic: the activities of overseas book donation

programmes, and their potential negative effects on the local book industries.

There are serious pitfalls as libraries across the African continent

increasingly rely on these book aid schemes in their hunger for books and to

fill their empty - at best scanty - shelves.

Mrs. Ofori additionally made the case, supported vigorously by moderator Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, for reading in the mother tongue. This is an idea gaining increasing traction continent-wide (and overseas) and is strongly advocated and systematically carried out by caucuses of Africa's literary youth with The Jalada Collective of writers at the vanguard of the indigenous language movement. Bakare-Yusuf pointed to the capacity of mother tongue reading to exponentially expand the reading culture. She called for reaching the full diversity of ethnic groups that exist across Africa. Lola Shoneyin generated much hope and excitement about the expansion of the reading culture in Africa when she spoke of the Right to Write project which she manages and which has been supported by a generous grant from the European Union. Established writers of children's books will mentor emerging writers. The books that emerge will be translated into the relevant ethnic tongues. Mrs. Ofori insisted that publishers must respond to this new movement, not only through the provision of print copies of books but by creating digital books and digital libraries. Clearly, she was not focused on the considerable costs of developing digital content which would render digital libraries a pipe dream for small independent publishers with limited resources and who still largely dominate the African book industry. A dynamic and vocal publisher, Lola Shoneyin spoke of her partnership with a bank for the purpose of digitisation, which made far more sense to the audience and raised far more hope. She has undertaken a state-of-the art book project in partnership with Sterling Bank of Nigeria. Her team of social entrepreneurs will produce books in a variety of cutting-edge print and digital formats for marketing across the country in a bid to expand the reading culture.

The last take-away of value from this panel was from Wale Okediran, host of the pioneering Ebedi Writer's Residency, a former president of Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) and retired parliamentarian. Okediran advocated stage and screen adaptations of books to draw attention to the book and to generate a wider readership and book sales. He cited one of his own books as having seen a significant spike in sales during the making of the film adaptation, that is, even before the film's release. An informal relationship between Nollywood and the African book industry for screen adaptations of books is an attractive idea.

Surprisingly, not a single panel member addressed the issue of publishing education and professional training on the continent. When an audience member broached the need for formal training in the sector, for improved editorial content and production quality, the panel's response was so lame, I cannot even remember it.

What the panellists did do well was to engage in an interesting debate about parity between print and audio books. Moderator Bakare-Yusuf argued for the supremacy of print/the written word, making an articulate statement: "lack of the written word in Africa has disadvantaged Africans historically. The possession of it will restore the place of Africans in global written history."

Panel Discussion 4: The Role of Technology in Overcoming Illiteracy and Promoting a Reading Culture.

With multiple award-winning debut novelist, Ayobami Adebayo, absent from the proceedings, this panel was moderated by Masennya Dikotla, CEO, Molteno Institute for Language and Literacy based in South Africa.

"Audio books are the new Netflix" said Ama Dadson of Akoo Books. She vaunted statistics for its market globally, up to $3billion, but was far less fired up about the statistics for the African market. I got the impression it was hard work selling audio books to the people of Africa though she insisted that mobile phone operators and influencers on social media were a powerful sales force. She expressed faith in what she was doing fuelled by the knowledge that her blind mother is a grateful beneficiary of the power of audio books to keep people reading even when they cannot. She would persevere.

Harry Hare of CIO East Africa, an IT Media company, talked boldly about 'disruption' of the kind spearheaded by Nigeria's Okada Books, 'the fastest growing mobile book reading app in Africa' reputedly. When Hare announced, "Let's stop talking about books, let's talk instead about content", my mind immediately went to the Panel 3 debate which had just taken place about the supremacy I want to see retained by the written word in conventional book form.

But Hare is a dynamic speaker. I listened as he disrupted, taking a counter-seminar position: "The reading culture is not low, people are reading more now. Publishers are struggling when they shouldn't be. They need to re-think their approaches to selling books".

Start with the user, he advocated, and then decide how best to channel content

to them. People will read if they are served literature in the formats they

prefer. Hare spoke energetically about the preference of millennials for

digital content, but was unable to respond to a journalist from The Bookseller

magazine who cut in from the audience to argue that print was just as popular

as digital with millenials, providing data to prove his point. A four time TEDx

speaker and one of 'Venture Africa's 40 African Innovators to Watch', Okechukwu

Ofili colourful co-founder of Okada Books, spoke confidently, rattling off

data to back his faith in an African future informed by digital books; boasting

of currently 208,000 Okada users and fast growing user rates. Like Hare, he

argued that it's untrue that people don't read: the problem is the serious

distribution problem books have. So how can you get books to people across

Africa, faster, efficiently? Answer: digital. Okada has made things far easy

for writers to digitise books, he added. Okada Books is the technology of

choice for writers with a niche appeal for selling their books. He supported

Hare's position about youth preference for consuming data, he made a loud call,

which got the audience laughing, for younger panelists and more youth

representation in the audience at future seminars. Godwin Fiagbor, Africa

Director for Educational Technology Solutions for Edify, called for

digitising rural Africa and reaching school children in difficult areas

world-wide by means of affordable offline technologies along the line of Okada

Books.

they are served literature in the formats they

prefer. Hare spoke energetically about the preference of millennials for

digital content, but was unable to respond to a journalist from The Bookseller

magazine who cut in from the audience to argue that print was just as popular

as digital with millenials, providing data to prove his point. A four time TEDx

speaker and one of 'Venture Africa's 40 African Innovators to Watch', Okechukwu

Ofili colourful co-founder of Okada Books, spoke confidently, rattling off

data to back his faith in an African future informed by digital books; boasting

of currently 208,000 Okada users and fast growing user rates. Like Hare, he

argued that it's untrue that people don't read: the problem is the serious

distribution problem books have. So how can you get books to people across

Africa, faster, efficiently? Answer: digital. Okada has made things far easy

for writers to digitise books, he added. Okada Books is the technology of

choice for writers with a niche appeal for selling their books. He supported

Hare's position about youth preference for consuming data, he made a loud call,

which got the audience laughing, for younger panelists and more youth

representation in the audience at future seminars. Godwin Fiagbor, Africa

Director for Educational Technology Solutions for Edify, called for

digitising rural Africa and reaching school children in difficult areas

world-wide by means of affordable offline technologies along the line of Okada

Books.

With Okechukwu Ofili of Okada Books and Harry Hare of CIO East Africa dominating discourse, it was a highly engaging panel. Two clear, concise conclusions that I took away were: (1) Publishers need to trust digital and to push it as hard as print and at the same time. (2) With the help of IT experts to facilitate the transformation. African publishers must at least partly go digital using business models tailored to meet their needs.

Panel Discussion 5: Addressing Freedom to Publish Challenges in Africa.

Moderated by Folu Agoi, past President of Pen Nigeria, out of the six panels, this one meant the most to me. Why? Because the perception of political correctness as a stronghold to be overthrown, was a powerful selling point of Donald Trump's bid for the presidency of America and was supported in no small measure by white evangelical Christians across the country. And, shockingly to me, evangelicals right here in Africa. They are in fact a global demographic of fierce proponents of individualism, standing firmly by the anti-censorship position of Christian theology that exalts the dignity of the individual, rejecting censorship which it believes abrogates that dignity.

I wanted to understand the principles of the debate between freedom of speech and censorship/political correctness. I wanted to be able to envisage Trump's America, and a Trumpian world totally unshackled from the chains of censorship and to decide whether or not I like it.

As part of the opening of the discussion, Kristenn Einarsson, Chair of the

International Publishers Association's Freedom to Publish Committee,

recognised Reporters without Borders with great respect. The international

human rights agency rates the adherence to freedom of speech of countries

across the globe and publishes three different indexes annually of the best and

worst countries in this regard. I was particularly struck by Mr. Einarsson

exposure of government proposals for government-led educational book publishing

as a subterfuge to control what children imbibe. The citing of an economic

justification for taking charge of educational publishing, he argued, is always

a lie of governments worldwide, a lie of authoritarianism that the Freedom to

Publish Committee would continue to expose. He presented the mandate of the

committee which is to advance the freedom to publish and to celebrate champions

of freedom such as Zimbabwean news media baron Trevor Ncube, (Alpha Media

Holdings) who won the International Publishers Association Freedom Prize in

2007. The prize was awarded for Ncube's fearlessness in journalism in a

Zimbabwe groaning under the dictatorship of Robert Mugabe. A major aim of the

IPA's prize is to protect persecuted publishers by raising their global

profile; a clearly successful strategy demonstrated by Trevor Ncube's presence

on the panel. A commanding personality, Ncube regaled the audience with tales

from his impressive life protesting and publishing honest news with his

personal freedom constantly on the line.

As part of the opening of the discussion, Kristenn Einarsson, Chair of the

International Publishers Association's Freedom to Publish Committee,

recognised Reporters without Borders with great respect. The international

human rights agency rates the adherence to freedom of speech of countries

across the globe and publishes three different indexes annually of the best and

worst countries in this regard. I was particularly struck by Mr. Einarsson

exposure of government proposals for government-led educational book publishing

as a subterfuge to control what children imbibe. The citing of an economic

justification for taking charge of educational publishing, he argued, is always

a lie of governments worldwide, a lie of authoritarianism that the Freedom to

Publish Committee would continue to expose. He presented the mandate of the

committee which is to advance the freedom to publish and to celebrate champions

of freedom such as Zimbabwean news media baron Trevor Ncube, (Alpha Media

Holdings) who won the International Publishers Association Freedom Prize in

2007. The prize was awarded for Ncube's fearlessness in journalism in a

Zimbabwe groaning under the dictatorship of Robert Mugabe. A major aim of the

IPA's prize is to protect persecuted publishers by raising their global

profile; a clearly successful strategy demonstrated by Trevor Ncube's presence

on the panel. A commanding personality, Ncube regaled the audience with tales

from his impressive life protesting and publishing honest news with his

personal freedom constantly on the line.

Speaking at great length, unexpected in panels of this nature, seasoned

journalist, Festus Adebayo, explained issues pertinent to the freedom to

publish and detailed libel and its laws. He argued sternly for the safeguarding

of decency and humanity by banning certain publications.

At the close of the discussion I was still of two (or more) minds about total

freedom of expression, and will need to wait until my planned interview with Kristenn

Einarsson of the IPA's Freedom to Publish Committee before I can form a clearer

judgement.

Panel Discussion 6: Enhancing Enforcement of Copyright and Intellectual Property (IP) Laws.

The discussion did not actually cover Intellectual Property (IP). Instead, Laurence

Njagi, Chairman of Kenya's Publishers Association, moderator, limited it to

the enforcement of copyright and piracy, copyrights biggest threat.

Njagi was dramatic in his opening speech. "Let's call pirates what they are: thieves, armed robbers... Books are light," he said. "Let pirates destroy publishing and darkness will fall on us all".

Then he made two statements that many outside the publishing industry should

(but will regrettably not) be surprised to hear: large numbers of school books

in Africa are in fact pirated copies with some unscrupulous booksellers serving

as a conduit for piracy.

What followed were vigorous responses from panellists to related questions

which he moderated ably, for example:

Are copyright laws in our countries strong enough to protect us?

After some discussion and debate, John Asein, Executive Director of the Reproduction Rights Society of Nigeria exposed the lack of clarity about (i) book policies in the country: how is the book industry supposed to run? Is there a real book policy - one that is practiced? And (ii) reporting mechanisms for piracy, which persists in Nigeria: Which minister do we run to?

Final answer: Yes, copyright laws are strong in our various

countries, but are they actually implemented?

Do booksellers have codes of conduct and how can we improve the ethics of

booksellers?

In response, John Asein, Executive Director of Reproduction Rights Society

of Nigeria, called for structures and synergy and for safe corridors

within the country and across Africa through which books are sold. Accredited,

well-known corridors. There must be a policy about where and how books are to

be sold. If you fail to follow that protocol, it should be assumed that your

books are pirated copies. We need effective collaborations with relevant

agencies at our borders to combat piracy.

Pirated goods coming from outside come in through the same route as legitimate books so how do we protect ourselves against pirated books coming from outside?

Afam

Ezekude, the Director-General of the Nigerian Copyright Commission (tellingly the only  government

representative on any one of the six panels), presented the mechanisms in place

to counter copyright violations. He made the powerful claim that in the seven

and a half years since taking office, the NCC has made seizures of pirated

goods to the value of N10 billion. The NCC, he explained, arrests and

prosecutes suspects through the justice system and book pirates have in fact

been sentenced to prison without the option of fines. Working with relevant

stakeholders such as the Nigeria Police Force and Customs Services has

strengthened the NCC's ability to stymie the scourge of piracy. By way of

evidence to support the book industry as it raises the alarm about piracy's

terrifying capacity to destroy it, Ezekude cited a recent example of a seizure

of twenty eight containers, of which twenty contained pirated books.

government

representative on any one of the six panels), presented the mechanisms in place

to counter copyright violations. He made the powerful claim that in the seven

and a half years since taking office, the NCC has made seizures of pirated

goods to the value of N10 billion. The NCC, he explained, arrests and

prosecutes suspects through the justice system and book pirates have in fact

been sentenced to prison without the option of fines. Working with relevant

stakeholders such as the Nigeria Police Force and Customs Services has

strengthened the NCC's ability to stymie the scourge of piracy. By way of

evidence to support the book industry as it raises the alarm about piracy's

terrifying capacity to destroy it, Ezekude cited a recent example of a seizure

of twenty eight containers, of which twenty contained pirated books.

A very brief, open-ended discussion followed about adopting the pharmaceutical industry's tactics for protection against fake products.

Final answer: A lot of work still needs to be done here.

What does the acronym GAFA stand for and what is it position on copyright?

Jose Borghino, Secretary-General of IPA first referenced the Berne Convention on Copyright and the historical relationship with the IPA, before speaking passionately about the harm dealt to copyright by Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, GAFA's constituent corporations [the four most powerful American tech companies]. The GAFA corporations, he explained, have made copyright seem not in the public interest; as an impediment to creativity; old and out-moded, not sacred at all. He argued that copyright is someone's intellectual property that publishers make tangible and saleable and that "stealing is stealing". Reminding the audience that copyright is a child of the 17th century Age of Enlightenment, he stated that it is the basis of much of human creativity. Supporting John Asein who referred to 'the copyright system [as] the soul of publishing', Borghino insisted that it is the best possible system for authors and publishers, deserving of all possible protection. He emphasised the often very poor quality of pirated products as something that should be publicised, to deter the consumption of pirated goods.

How do local printers protect themselves from printers in China and India

taking their business?

Final answer: We need to improve the quality of local printing.

This question was particularly interesting to me as I had been approached by an Asian businessman in the audience who had travelled all the way from home in search of printing deals. Watching him work the IPA/NPA seminar hall looking for customers, I was astonished by his focus and his tenacity. He gave me two business cards.

Today is Thursday, 17 May 2018. The first ever summit of the IPA to be held in Africa took place over a week ago. While waiting for a copy of the NPA's Lagos Action Plan 2018, I will conclude my event report with one brief commentary.

The first is from Gbenro Adegbola, Managing Director/CEO of First Veritas, an educational technology company, and former Managing Director of Evans Publishers, Nigeria. I asked him about the emphasis put on foreign domination of publishing in Nigeria after the panel discussion on Strengthening Educational Publishing in Nigeria and about his views on the entire proceedings:

"Foreign domination of publishing in Nigeria is a non-issue really. This is speaking for Educational publishing. And I think it crept into our discussions from a misunderstanding. Apart from the two rounds of indigenisation of Nigerian businesses by law in the 70s we have seen lately a willing dilution of foreign owned shares in a number of companies and outright divestment in at least one. Since the 80s, several companies have come up that have become great institutions today, such as Spectrum Books and Lantern Publications. The last 17 years of democracy and the resultant stability in the economy and polity coupled with the significant growth in school enrolments have witnessed the biggest growth in the history of the Nigerian publishing industry, at least in terms of the number of new entrants into the business. Unfortunately, there was little time to deal with other issues. One which I've been thinking of a lot is how we can deepen the market. Even with the growth in numbers of new firms, I doubt that we have significantly widened the market. The seminar has started a conversation which should go on among ourselves with a view to addressing and resolving some of these issues." (Gbenro Adegbola, First Veritas)

I am drawn to people of mixed-cultural descent and of mixed-race heritage. I'm also drawn to ...

David Aguilar, born in Andorra, is an inspiring figure known for his resilience and crea ...