But underneath that difference, the problem is still the same issue: how can the majority of people in Africa make decisions about their lives? That’s a problem that will have to be solved in the 21st century.

One of the political leaders you and Marika Sherwood profile in the biographical record Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787 is Oladipo Felix Solanke Founder, West African Students Union (WASU). Share some important themes and elements from his background and experiences which in your view led to the formation of the iconic students’ union.

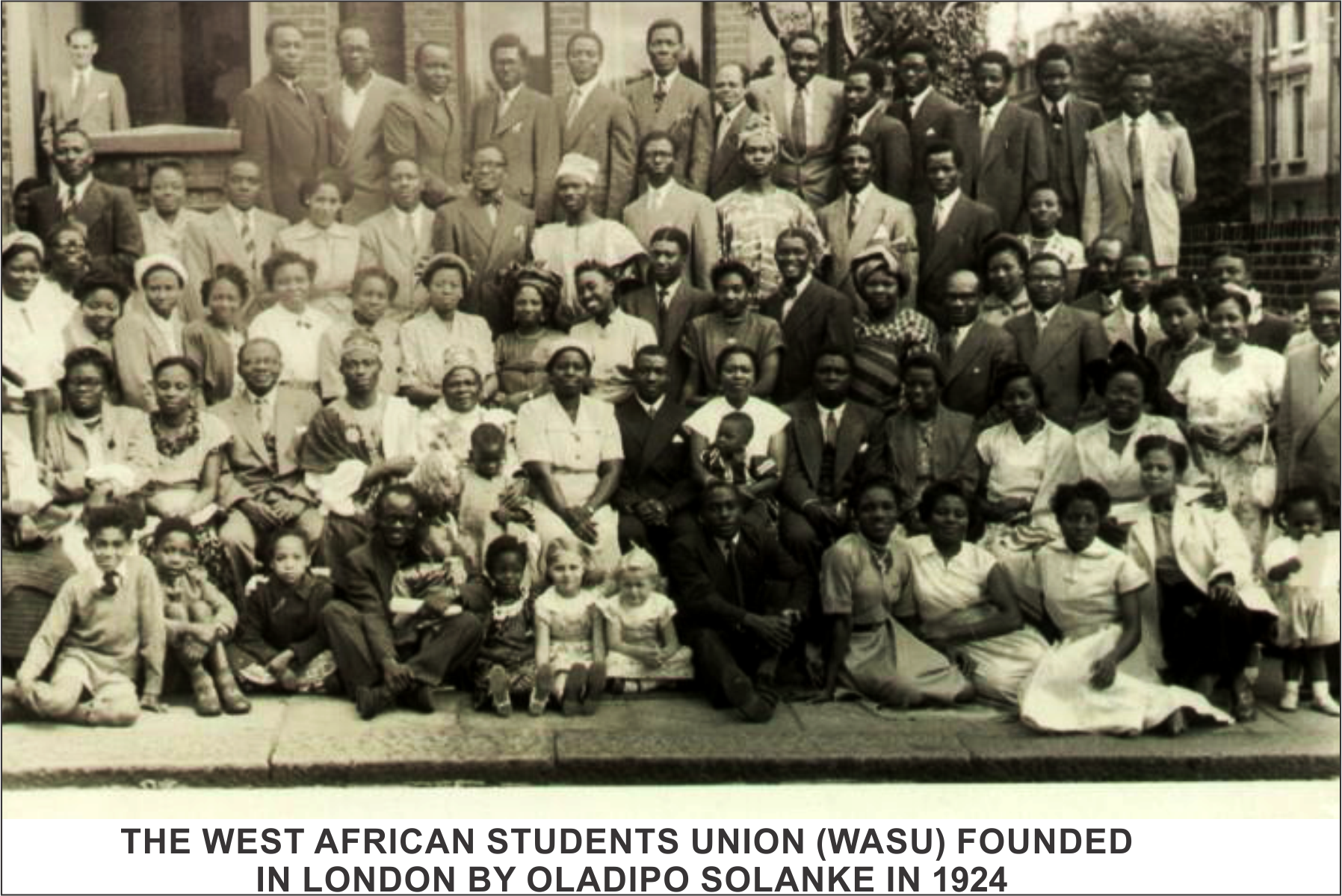

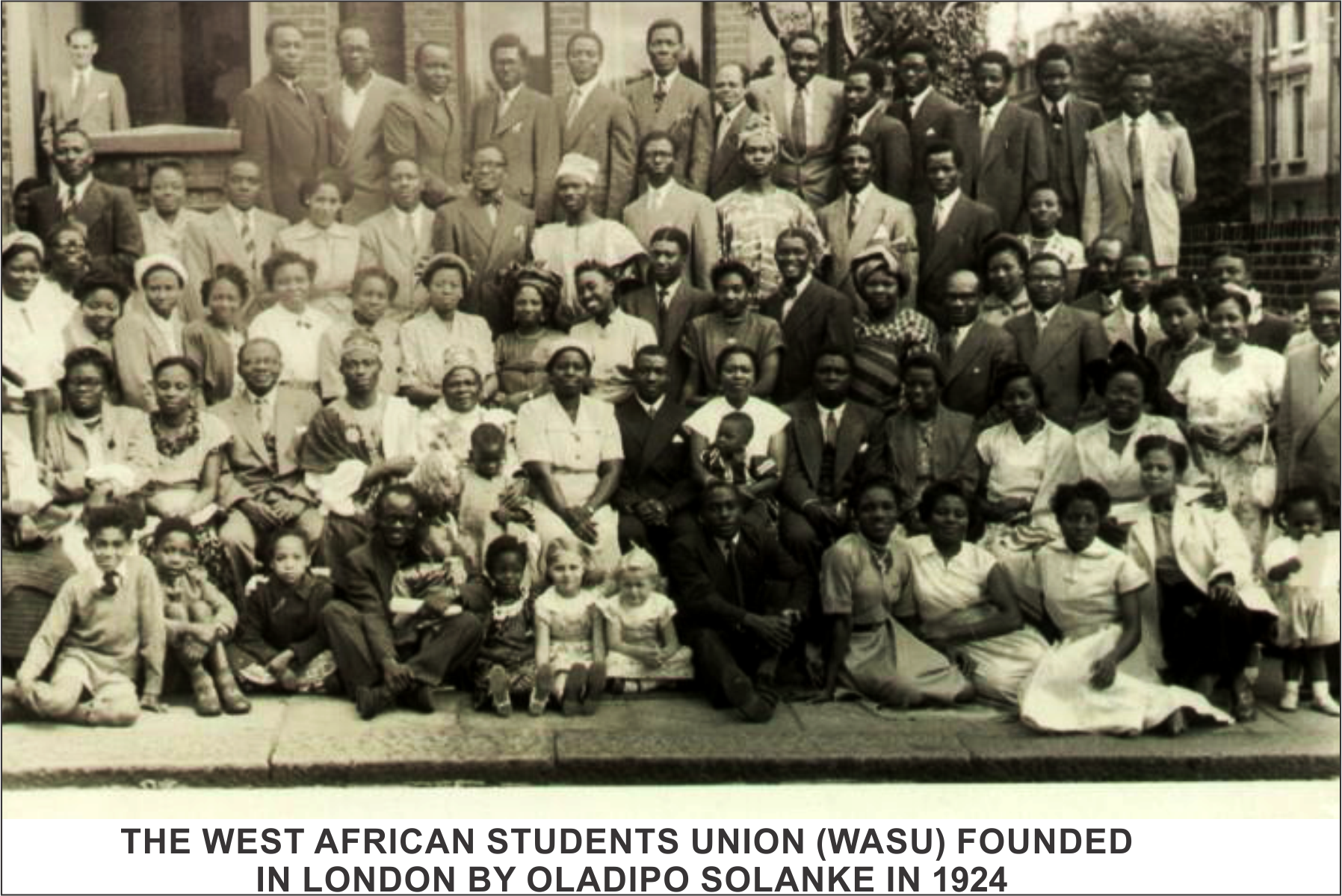

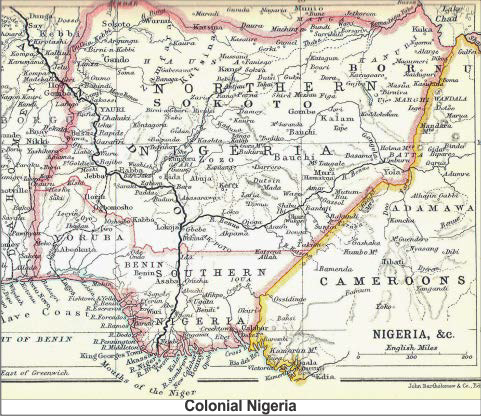

Solanke was a law student in Britain and was motivated to deal with two main problems: racism and colonialism. He founded two important organisations. One was the Nigerian Progress Union which he founded in 1924 with Amy Ashwood Garvey, the first wife of Marcus Garvey. So that was a Nigerian organization in London but it excluded other West Africans. At the time, there was an organization called the National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA) formed in 1920. It was an early anti-colonial organization. Well, it was not that anti-colonial but it was an attempt of educated people in the four British colonies to get together and speak with one voice about things that concerned them. They wanted to get involved with government in taking decisions etc. So NCBWA was influential. Solanke and others thought it would be good to have something similar in Britain and so in 1925 they founded the West African Students Union (WASU).

The other motivation for the foundation of WASU, was to deal with some of the problems that Africans faced in Britain. At that time, racism was legal. There was a colour bar and it was difficult to get accommodation and there were other related problems, and of course they were concerned about colonial rule itself. The idea was to establish an organization which could unite all West Africans to deal with problems of racism and to campaign. It would be a sort of pressure group in London which could convey to the colonial government, some of the concerns of the people in West Africa. Over the next 30 years, WASU developed in various ways and was still in existence when Solanke died in 1958.

Share some of the landmark moments from WASU’s history with us.

There are several. An important point is that the West African Students Union had its own parliamentary committee in London. In other words, if there was a problem in Lagos, somebody would send a telegram to WASU. WASU would take it to their parliamentary committee which was made up of MP. And the question would be asked in the House of Commons the same day or the next day. So that was an important landmark that was established during the 1940’s, that was very important. And then WASU also set up its own branches in West Africa. One in Nigeria, one in the Gold Coast, Gambia and in Sierra Leone. They functioned as kinds of embryonic anti–colonial organizations in those countries. When the Nigerian Youth Movement was formed in Nigeria, it was based around the WASU branches. WASU was an important organization with connections in Britain and in countries throughout West Africa. It was really the first organization to demand an end to colonial rule. And in fact, before the people of Nigeria demanded independence, the West African Students Union demanded it.

It’s fascinating to hear about the powerful role WASU played in pre – independence Nigeria. I don’t think the students are as empowered now. Do you follow student activism on the continent?

I follow some of it. Well it’s problems are different now. There are different distractions. And certainly, they have always attempts to subvert students’ movements. There were attempts even at that time to keep WASU in certain channels but it managed to find its way out. In those days, it was clear who the enemy was. Maybe it’s not quite so clear today which makes it easier to divert students’ movements into other channels.

In your essay in the African Studies Review (Volume 43. Issue 1), you explain that in Imperial Britain, there were “attempts to develop a class of Africans who would be sympathetic to the interests of the British ruling class, attempts which were very much in evidence during the twentieth century.â€

Talk to us about this and about the ‘defenders of the empire’ who monitored the African students activities and ‘closeted’ them away from ‘subversive influences’. Who were these ‘defenders of the empire’? What were these ‘subversive influences’?

One of the problems that faced the African students in particular, was finding somewhere to live because there was what was called a colour bar in Britain. This meant that if you were a person of colour from Africa, either you would be unable to rent a room or you would have to pay much more. So the government saw that there was a problem of racism. They thought If we the government don’t do something, these African students will become disaffected, go back to Nigeria, and hate Britain. They will be more militant. We have to do something about it. They took measures to set up various hostels for the students to stay in.

The idea was that if they were comfortable, if they had a nice room to stay in, they would stop being political. It didn’t work like that in the end. The students to some extent rejected these attempts and set up their own hostel called Africa House where they could do what they wanted to do.

So providing good accommodation was one way the colonial government tried to influence the direction of the African students. Another way was connecting the African students to the wealthy people who would invite them tea, look out for them, that kind of thing. They encouraged them to join organizations and societies and later on there were scholarships and other placebos in an attempt to keep the African students from the three subversive influences: racism, communism and white women.

White women were a subversive influence? How?

The main problem was that the Africans would actually get married to these white women and take them back to Nigeria or wherever. That was problematic because over time, it would undermine the entire racial colonial order which had Europeans at the top and Africans at the bottom.

I am fascinated by this women thing because it is very difficult to keep men away from women. How do you keep men away from women?

You cannot keep men away from women. Of course you can’t. It is an impossibility but it was an aim of the Colonial Office to try and steer students. It was no easier than trying to keep them away from racism. How do you keep someone away from racism when you are in Britain? It is not possible and of course the students were not only reacting to the racism of being an African in Britain but of being an African in Africa. Colonial rule itself was racist. The Colonial Office recognized the problem: if the students kept coming up against racism in Britain, they would become more militant and more determined to put an end to colonial rule.

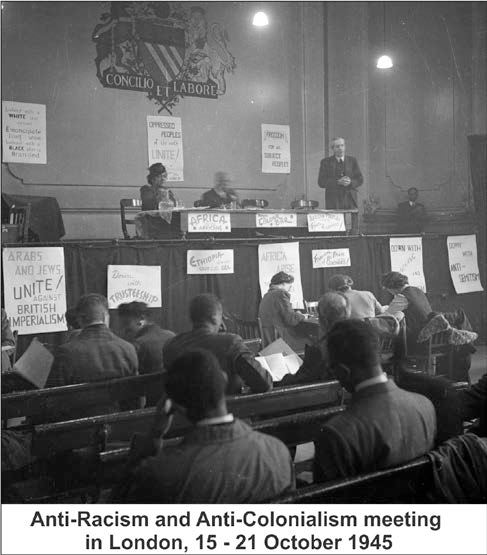

And then there was communism which they found it difficult to keep the students away from because the communists were the only political organization opposed to colonial rule. So naturally the students gravitated towards communism and the communists gravitated towards the students. There were all kind of discussions often over Aggrey House.

What was the cause of the infamy of the student’s hostel called Aggrey House?

It was a secret scheme by the government to provide a hostel for African and Caribbean students.

The aim was to give them a nice environment and keep them away from the three subversive influences but it was set up secretly because if the Africans knew it was a government hostel, they wouldn’t use it. The students wanted to be independent; they didn’t want to live under the auspices of the colonial government whose aim was to monitor them whereas the students aim was to keep away from being monitored.

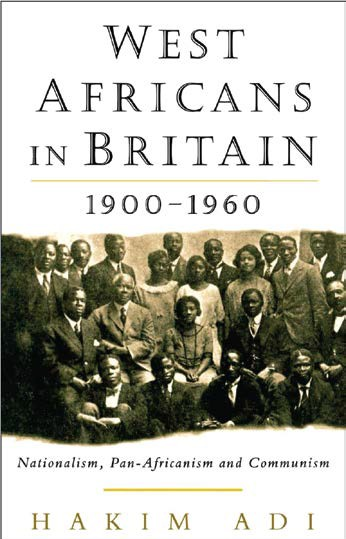

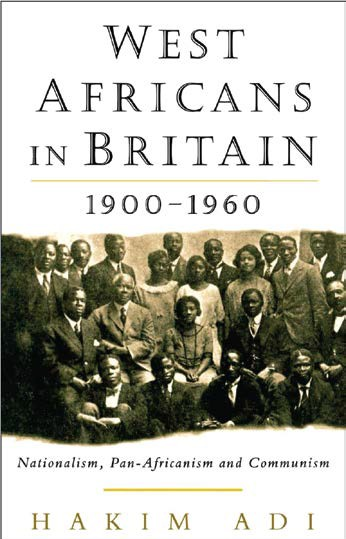

The West African Students Union was already suspicious of Aggrey House when it was announced, so Solanke was sent back to Africa to raise money. He travelled throughout the four colonies for 3 years, collected money and came back to Britain. WASU was now able to set up their own Hostel in a rented house so that when Aggrey House opened Africa House already existed. WASU announced that everyone should boycott Aggrey House because it was a government institution. There was long running dispute throughout the 1930s which was finally resolved and the powers that be began to give some funding to the WASU. It was very good at doing its own thing and also at taking money from the government if it was on offer. In my book West Africans in Britain I explain all this in detail.

In 1924, the Nigerian Progress Union (NPU), was founded by Ladipo Solanke and Amy Ashwood Garvey, (estranged wife of Jamaican political activist, Marcus Garvey). In 1925, the NPU published an ‘Open Letter to the Negroes of the Worldâ€. This letter viewed Nigeria as the centre of the pan-African world and as a country

‘full of immense possibilities’ and ‘underdeveloped sources of wealth’ that might one day become ‘a mighty Negro empire or republic.â€

How hopeful are you about Nigeria’s pivotal role in Africa almost a century after the Open Letter was published to the ‘Negroes of the World’? Talk to us about possibilities of and challenges to the progress of Nigeria in 2020 and beyond.

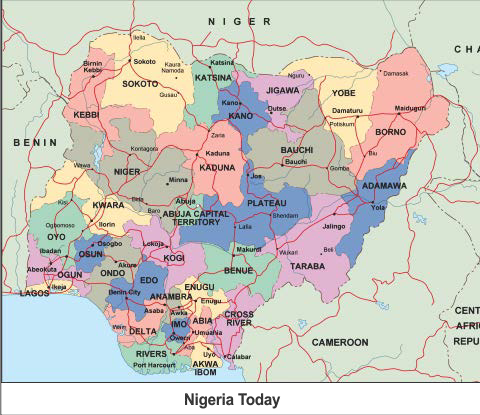

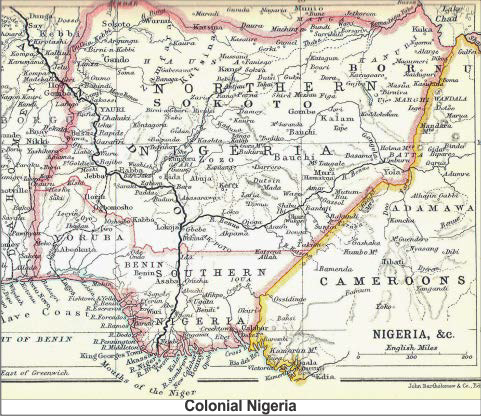

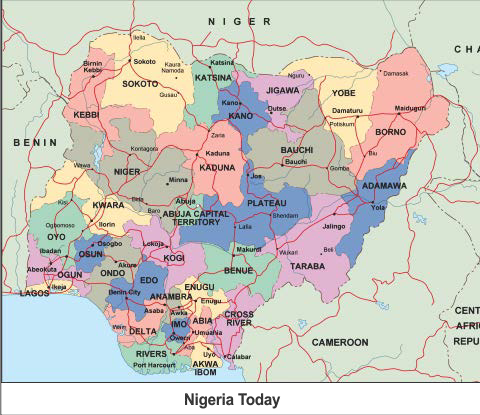

You are better placed to know the challenges, but of course the potential of Nigeria is immense. It is Africa’s largest economy. It is Africa’s biggest country in terms of population. So there is potential to be a world leader of Africa. But it is a mess. All the ingredients are there: one of the world’s leading oil producers; it has a massive population; it has one of the largest rivers in the world. However, is it realizing this potential when we have a country in the 21st century that cannot supply its residents with electricity or clean drinking water or kerosene?

We have to be concerned about why Nigeria hasn’t realized this potential. One of the reasons is that the direction of the economy has not changed since the time of colonial rule. That is to say that the majority of people in Nigeria, basically a billion?? people, have no decision-making power. How the country develops is based on decisions made by a very tiny group of people. Just as during the colonial period. The great human potential is powerless to decide how the country should develop. The challenge is how to involve and mobilize this massive creative force which are the citizens of Nigeria. If that human factor can be organized, mobilized and unleashed, then the possibilities are endless. But what is the orientation of the economy ? If the orientation of the economy is to look after the interests of the people , it would be impossible to have the current situation. If the orientation of the economy is to make money for a small number of people, then everything can be explained.

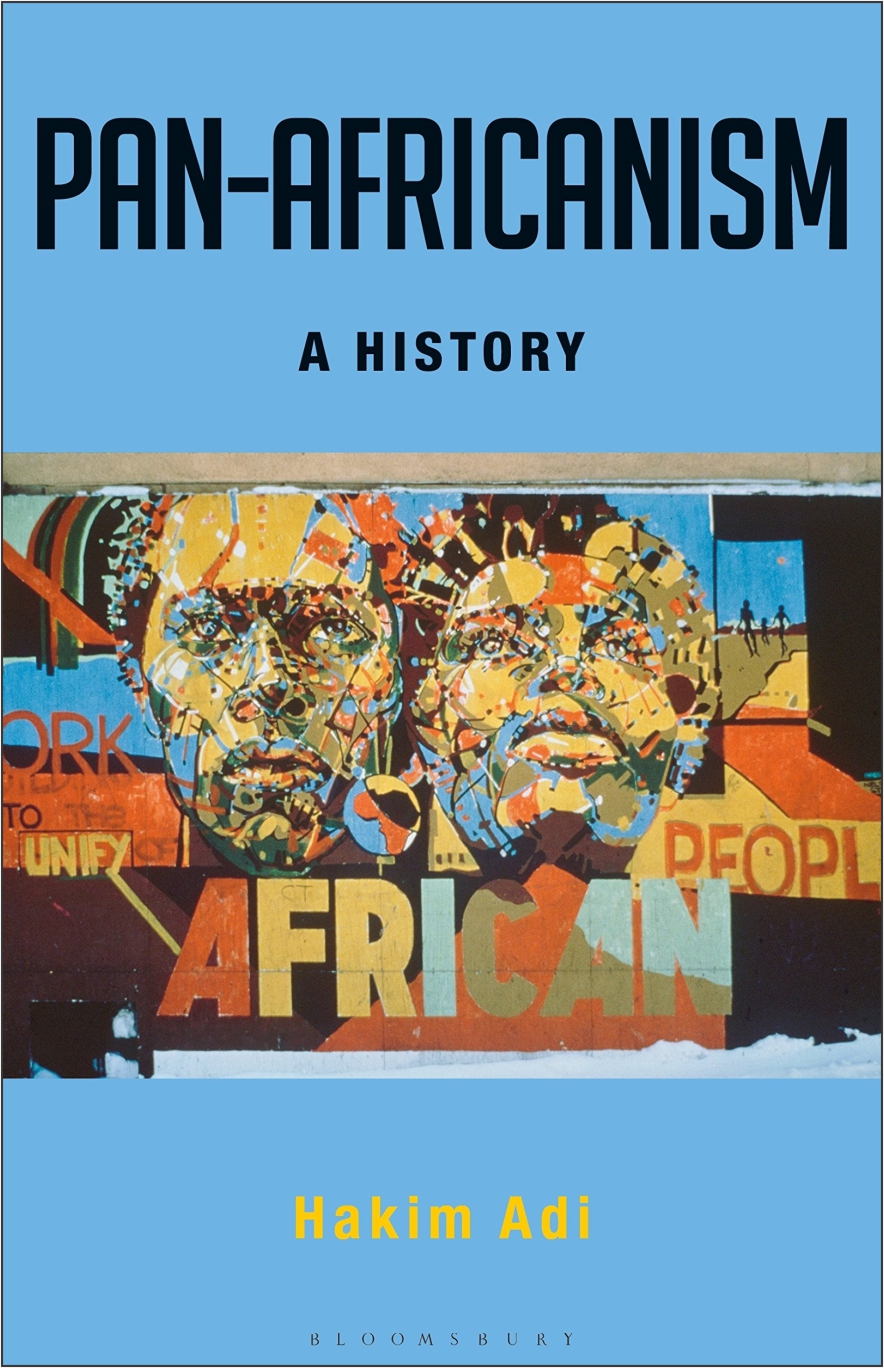

A major set-back for high-achievers of African heritage, is marginalisation: being kept out there in the shadows. What you are doing as you write your history books is bringing great African leaders into the light – into the mainstream - so they can take their place in world memory. I’m very pleased Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787, the biographical record you wrote with Marika Sherwood, is downloadable online as a pdf.

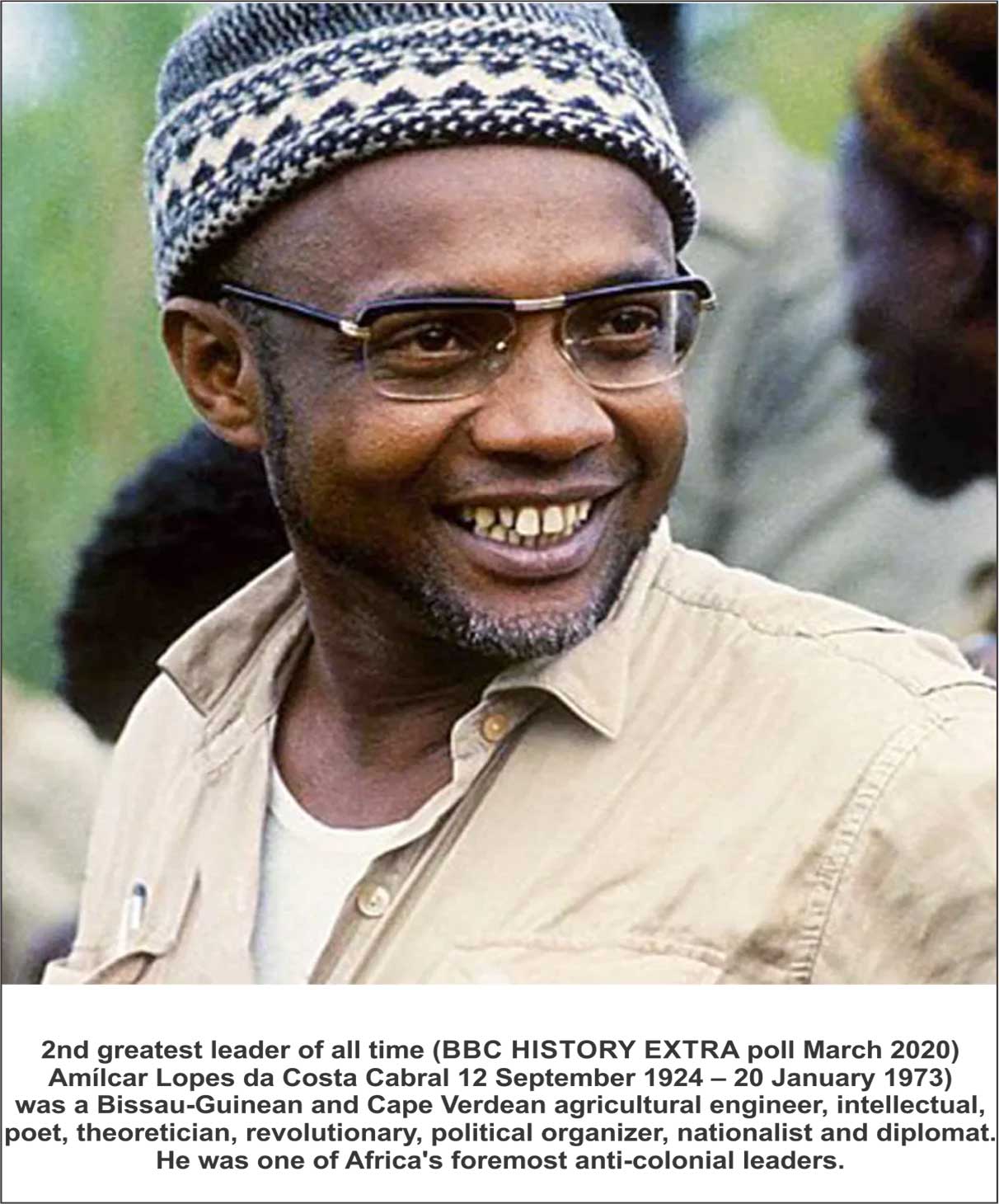

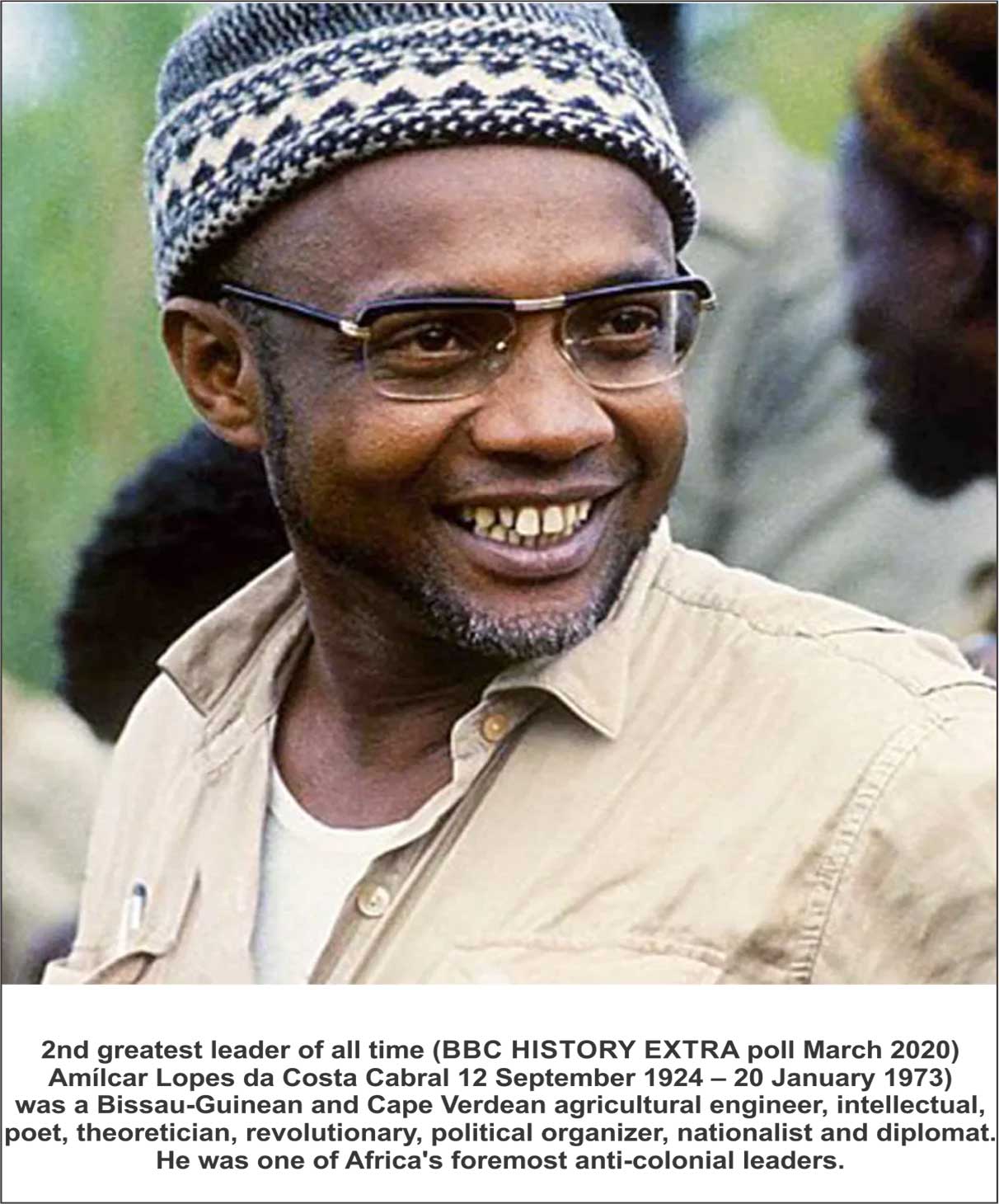

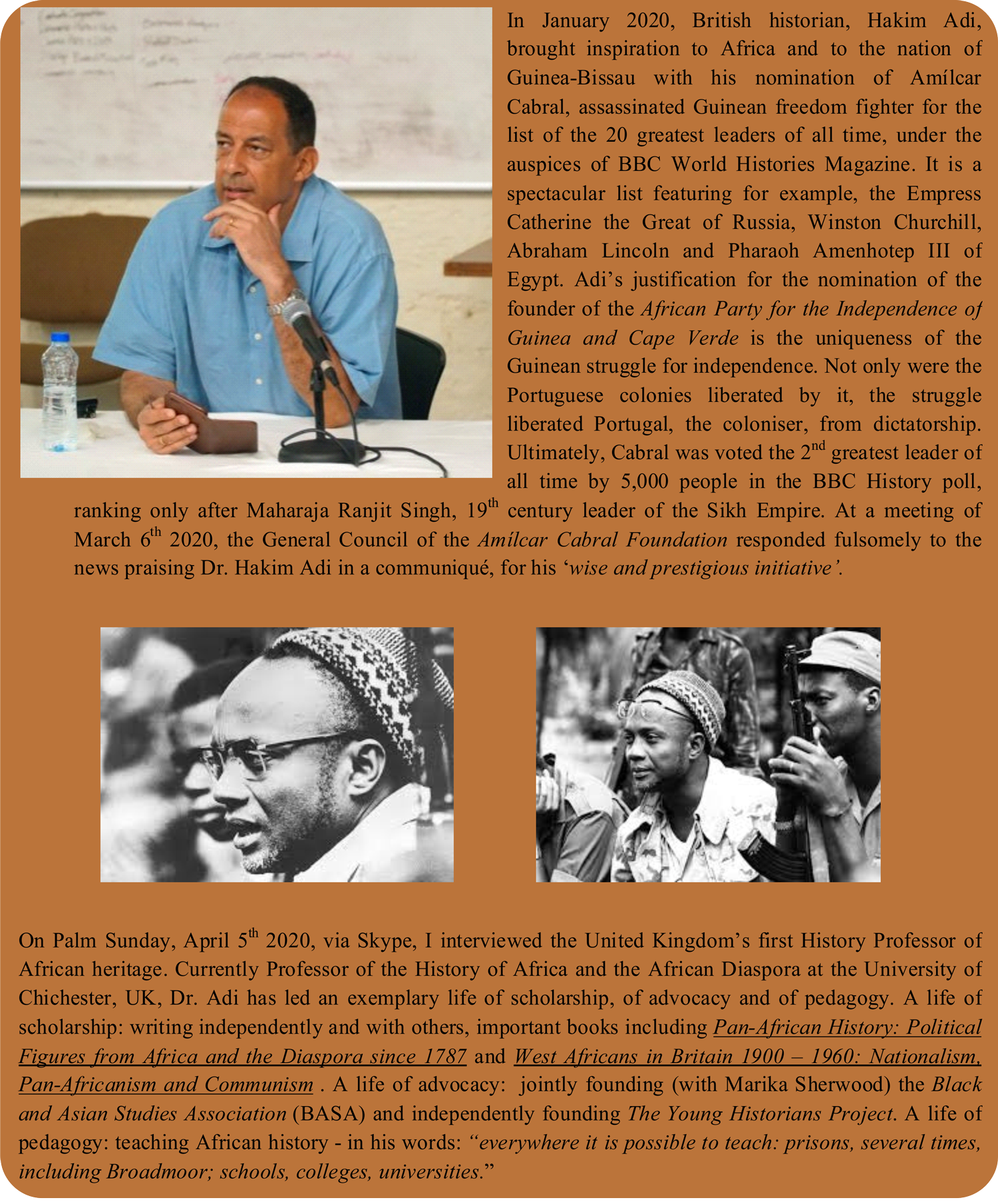

You were one of a panel of leading historians invited by the BBC History to present nominations for its 20 greatest leaders list in January this year. Tell us something about your nominee, AmÃlcar Cabral, who was ultimately ranked the 2nd greatest leader of all time by 5,000 voters.

I was given very few words to talk about Cabral. There was a big article next to it about Catherine the Great so I complained: why was this important African being discriminated against? He was the inspirer and leader of the struggle for national liberation in Guinea and also in Cape Verde.

It was an extremely difficult anti-colonial struggle so that in itself is very important. But more than that, he gave an example of what a political leader should be: someone willing to sacrifice himself for the people. Of course he gave his life for that struggle. Someone who is of the people: concerned not about the rich but about the workers, the farmers. Thirdly, he had a vision of a new society in which people were at the center and they made the decisions. Very unlike most societies that exist in Africa or Europe. He was very inspiring throughout Africa and the world. That struggle not only led to the liberation of Guinea but it led to the fall of the dictatorial government of Portugal. His important role in the struggle for Africa's independence needed to be made more public.

Finally, you are the founder of the Black and Asian Studies Association (BASA) which I know has been discontinued but it did a lot of necessary work in its day. And also of the Young Historians Project in the UK. Talk to us about the objectives and about the urgency for these interventions and give us examples of projects undertaken.

BASA was founded in 1991 with the aim of encouraging the study of history of people of South Asian, African and Caribbean heritage in Britain. At that time, British history excluded people of colour. Other important objectives were to encourage research and interest in black history and to advocate for history to be taken more seriously by museums, archives and so on. We also campaigned for change in the school curriculum, at the primary and secondary levels, that it should include people of colour, a comprehensive representation of Britain which extended far beyond Empire Windrush, into the Roman times and beyond. Without seeing your own people documented in history, you grow up having a strange view of the world because it excludes us.

It is part of the racism we face...But young people who are not people of colour also need to know this comprehensive history. An example of forgotten or erased history is Septimius Severus, a Roman emperor who was born in Libya, of Berber origin. BASA held conferences for teachers who were also not educated about the need for comprehensive representation and with librarians, archivists, records office specialists about making sure records are properly catalogued that the history of people of colour in archives was not hidden.

We did serious work lobbying government through for instance meetings with the Minister of State for Education, at the time, Charles Clarke and with the Advisory Committee of the National Curriculum and a BASA member sat on the committee for about 15 years. Over that period the national curriculum did change and it became established that it would include people of colour.

When Michael Gove became Education Minister, he tried to reverse the changes but by then it had been established that history should be more inclusive and it was too late. Of course there is still much room for improvement.

I was one of the 4 members of BASA who created a new OCR GCSE course on the history of migration to Britain called: Explaining the Modern World: Migration, Empire, and the Historic environment. We also wrote a comprehensive textbook to accompany that course.

And The Young Historians Project?

The Young Historians Project arose from a conference that was held in 2015 called History Matters. It was a conference to discuss why so few young people or African or Caribbean heritage in Britain engage with history. That is to say, take history at exam level at 16 or 18 or go study history at university or as postgraduates students or become history teachers and so on. Very few young people engage in that way. On the other hand within the Africa and Caribbean population in Britain now, there is a great fascination with history.

All kinds of projects, websites, organizations and so on. So there’s a disconnect. The conference was convened to find out why that happens. We discovered a number of reasons. The main one is the same problem that faced me as a young person, which is that the history curriculum in schools, the social environment, and the media did not present the history of black people in Britain.

So the young people very often talk about a eurocentric history curriculum which puts them off. They think history is not about their families or ancestors. It’s about other people. The History Matters conference we convened discussed all these things and heard from school students, undergraduates, post-graduates, teachers and others. And then it resolved to address the problem. The Young Historians project for young people between the ages of 16 – 25 encouraged them to engage with history, to give them the skills for research and presentation to their peers.

The current project - which they chose themselves - focuses on African women in Britain: women from the continent or who are descended from parents from the continent. Women in particular who are connected to the National Health Service in Britain.

Many African women are nurses, doctors and have been for many years. However, when that history is presented in Britain African women are excluded from it. And they are never mentioned even when you go on Google to search for African women. So we are remedying that situation by researching the history of African women in Britain from c.1930 – 2000.

The young people have interviewed about 30 women now who were nurses, doctors, psychiatrist, health campaigners and activists. They will be producing a film, an exhibition, a mural, an e-book, a whole range of materials about African Women in Britain. In addition, they have found various historic personalities. One of the most significant is the famous: Nurse Denrele Ademola, the daughter of the Alake of Egbaland. She came to Britain to study nursing in the 1930 – 1940’s and attended the coronation with the Alake. A film was made about her as a nurse but unfortunately that film has disappeared. It was made in 1942. We are searching for it. It does not exist in Britain. We need to know whether it exists in Nigeria or anywhere so if you or anyone can help us find that film, we would be very grateful. It is the only film ever made of an African nurse or an African woman in Britain.

Hakim Adi, this has been a rich and inspiring conversation. Thank you for coming on Borders.

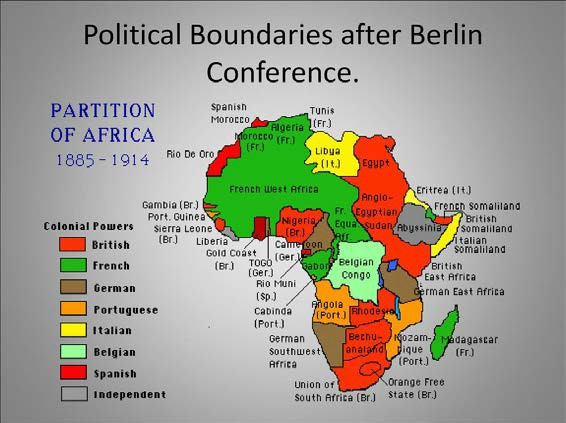

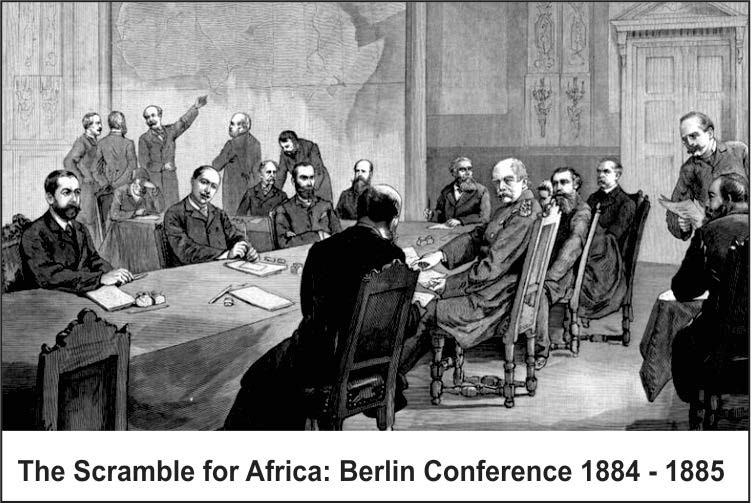

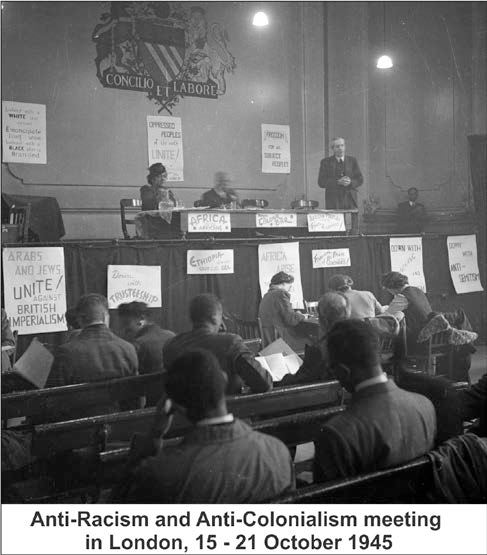

s on Africa. The problem confronting Africa in the first half of the 20th century was colonialism, colonial rule. Africans did not have sovereignty; they were deprived of decision-making powers about everything, whether politically, culturally or economically. Nearly all the countries of Africa were dominated and ruled by the big European powers in the interests of Europe. And the Pan–African movement addressed that in various ways. Initially it did that by requesting that the colonial powers should be more concerned about the majority of the people in Africa rather than just their profits and gains. Then in the second half of the 20th century, in the 1940s onwards, Africans began to demand an end to colonial rule, to unite together, using force if necessary, to end colonial rule. In most places, as a result of those struggles the whole continent is now in the hands of Africans. At least it appears that way.

s on Africa. The problem confronting Africa in the first half of the 20th century was colonialism, colonial rule. Africans did not have sovereignty; they were deprived of decision-making powers about everything, whether politically, culturally or economically. Nearly all the countries of Africa were dominated and ruled by the big European powers in the interests of Europe. And the Pan–African movement addressed that in various ways. Initially it did that by requesting that the colonial powers should be more concerned about the majority of the people in Africa rather than just their profits and gains. Then in the second half of the 20th century, in the 1940s onwards, Africans began to demand an end to colonial rule, to unite together, using force if necessary, to end colonial rule. In most places, as a result of those struggles the whole continent is now in the hands of Africans. At least it appears that way.