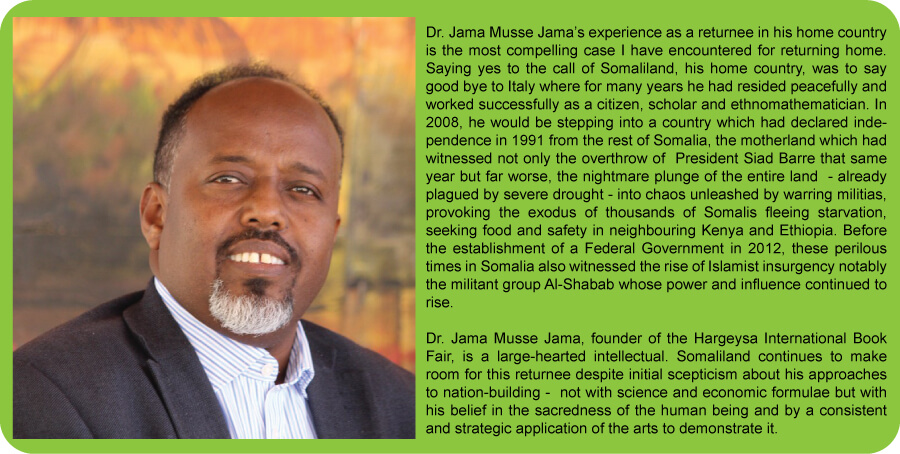

You are a polymath, a man of many talents and parts but I am fascinated by your designation as an ethno-mathematician.

Explain what an ethno-mathematician does, how you became one and how you are currently applying those skills.

Ethnomathematics is a branch of mathematics, relatively new, that explores maths beyond the canonical Western mathematics. It is a way to humanize the science and maths and to be culturally sensitive and ethically correct in knowledge production, knowledge dissemination and recognition of human wisdom, despite the geographical differences. Years ago, I asked myself what are the typical global examples used in all worldwide textbooks to teach probability in our schools? All of them use the game of dice and the game of cards. I then thought of an African child who never heard game of dice or a Somali mother who thinks that a playing cards is a sin (because it is linked to the gambling). I asked myself whether I need to teach the African kid the game of dice first and then mathematics, or should I teach the probability first then she may become an expert of games of fortune? Then I asked myself why not find culturally sensitive, locally rooted traditional games equivalent to the Western games to teach the very same mathematics in our schools and to incorporate them into the formal curriculum. Out of those questions, I produced my first article on Ethnomathemics "The Role of Ethnomathematics in Mathematics Education: Cases from the Horn of Africa Ethnomathematics", ZDM/99 in 1999. I followed this up with two books. One African traditional games and their use in math teaching "Shax: the preferred game of East African camel herders", (2000), and in Italian "Layli Goobalay: Variante Somala del gioco tradizionale Africano [Layli Goobalay: Somali variant of African National Game], (2002)". Other more sophisticated examples can be found in my subsequent writings, for instance "The Zeno's Paradox in Somali Culture and other stories", 2015.

You are wellknown as a brilliant and large-hearted arts administrator.

Share a few educational and professional landmarks that define the path to your renown in arts administration.

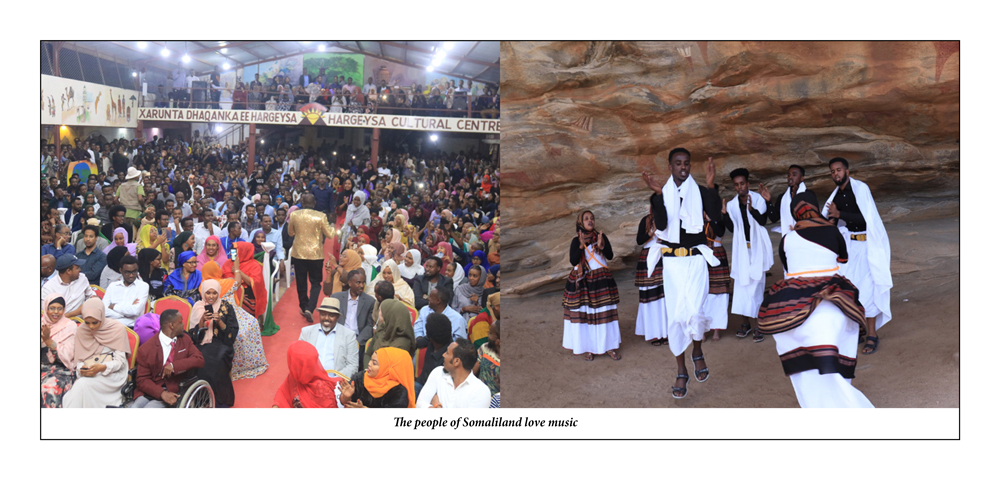

From my early boyhood, as I well remember, I had an aptitude for arts; and even after completing my higher education up to the university level, that inclination only increased in intensity. Of course, during my university studies my major subjects were hard science and mathematics. So also was my profession after graduation, I became a teacher in mathematics followed by high position in ICT in one of the major telecommunication companies in Italy, the country that had granted me its citizenship. Some years later in early nineties of the past century, having seen and felt the socio-political turbulence raging in my country, Somaliland, I decided to make my humble contribution in the rebuilding process that had been launched. Like it is in almost all African countries, the ruling authority in Somaliland then put their greatest emphasis, after successful reconciliation efforts among its population, on providing security and the basic necessities such as housing, infrastructure, employment, health and education, etc., neglecting the significant role of arts, literature and culture in the state building process. Owing to my deep conviction that arts and culture are what makes human beings more humane, my main engagement was in this sphere. Hence, the initiation of both the Hargeysa International Book Fair (HIBF) and Hargeysa Cultural Centre (HCC). To my delight and surprise I also eventually discovered that my educational background and professional career in maths and science, contrary to being an obstacle, were of substantial help in my current involvement in the arts and culture. In a nutshell, the development of arts and culture, in my opinion, is quid pro quo for the sustenance of a just, tolerant and harmonious society.

Last year, at Frankfurt Book Fair 2018, you were (as I was) a guest of Agence Culturelle Africaine at the Lettres d'Afrique: Changing the Narrative conference. You served on the panel about African book fairs and literary festivals. During your presentation you outlined the various tsunamis experienced by Somalia/Horn of Africa, and cited these as the reason for your inauguration of the Hargeysa International Book Fair. Tell us about these tsunamis and shed light on them as a key justification for your work at the HIBF.

Natural tsunamis obviously cause colossal damage and destruction to both human lives and material property. The process of reconstruction takes great efforts, finance, and a long period to recover from the tremendous loss suffered. So is the case, according to my judgement, with certain social events caused by the human beings themselves, whereby the magnitude of destruction is similarly enormous and the process of recovery becomes equally formidable.

The historical social events with magnitude similar to tsunami that affected the wider African society started with the slavery: A most horrific disaster. The modern world has not as yet adequately dealt with its grave impact, let alone making reparation to those countries that suffered most.

The second tsunami for Africa was colonialism: a mechanism that impoverished entire societies in terms of resources, destroyed their systems of governance and knowledge production, denigrated their art, culture and indigenous languages, and finally created such senseless and harmful borders and frontiers within and among the nations throughout Africa.

The third tsunami is the postcolonial injustice perpetrated by neo-colonialism by the super powers that continue perpetuate the impoverishment of the African countries by aiding and abetting the cruel dictatorial oppressive regimes that trample upon all norms of human rights.

The cultural hegemony practised by western developed countries in the 3rd world, including Africa, can also be termed cultural imperialism. Their sole aim is to maintain the exploitative system under different guises and to sustain the unequal relations between developed societies and the developing world. This cultural hegemony can be cited as the 4th tsunami.

The final and fifth tsunami now taking place, is the act of terror and the perceived war of counter-terror. This affects Moslem African countries in particular. For instance, the peaceful and progressive Islamic religion which is affected by the violent elements and their destructive ideologies. Additionally, the war between terrorism and Western counterterrorism usually transforms itself into another form of terror. This makes life hard for African people, particularly Moslem Africans. It creates an urgency to protect art, culture, indigenous knowledge and the philosophies of Africans. It creates an urgency to work on art and culture and to invest in our fragile society and to help transform from an oral to a written culture.

To combact such unequal relations and set things right, we need alternative policies and corresponding measures to be implemented. This undoubtedly, is a long and arduous process. But for the purposes of this interview, I can safely say that the crucial step is the realization of the huge damage wrought by this uneven relationship, its motivations and its methods of operation.

It is through this lens that I looked at my country Somaliland - and by extension the whole of the Horn of Africa region - and the misfortunes that have afflicted the region over the past 100 years.

In my country Somaliland, the people are still mostly under the grip of oral tradition, I see that the first steps towards development in all spheres of society presuppose the acquisition of literacy as a primary necessity. In this highly important process, the role of arts and culture becomes vital. This is where HIBF comes in and our collaboration and cooperation with other African organisations engaged in similar fields.

I know that you feel very passionately about colonial languages in Africa and about African languages. Let me reference Harvard Professor, Biodun Jeyifo's essay, 'English is an African language - Ka Dupe! [For and Against Ngugi] Volume 30 Issue 2 of the Journal of African Cultural Studies.

Although I am trained in different levels of English, Italian, and Arabic, my first language is Somali. Africa itself is not a country. Nullifying its diversity, making a homogenous, empowered, poor society, would create a sixth tsunami. But I understand Jeyifo's position to counter Ngugi's well-known position on the issue of languages.

The issue of languages in Africa for development is really complicated. If it is not tackled carefully and seriously it could easily lead into dire consequences. Approaching it from the basics, we know that every nation has its indigenous language(s). Language, apart from its role as the most appropriate means of communication, is also the main bearer or preserver of the nation's history and culture. As such, no to give the language its proper place in the overall development of the nation, would be a grave and dangerous mistake. Having said this, it must always be borne in mind that for the prospective development of the national language as well as the other spheres of the society, every African country is bound by necessity to gain the knowledge essential for its future progress, and this knowledge can only be gained through the acquisition of an advanced and developed modern language (whichever one: English, French, Chinese, Russian, etc.). It is not the foreign language per se that we are to guard ourselves against, but what it conveys and how it is manipulated for specific interests (whether by foreigners or national elites).

Putting it simply, the more you are educated and well-equipped through a modern language, the better qualified you are to further develop your own language, on condition that you have in mind the development of your own people. On the other hand, for the mass education needed, English or any language that is only for the elite will not help Africa get the knowledge it most needs. "Biyo sacabbadaadaa laga dhergaa" is a Somali proverb that roughly translates to "Only the water in your hands can quench your thirst".

It is not the language but what is being disseminated (ideas, opinions, policies, thoughts) and the aim behind the whole policy. Languages are not at all antagonistic rivals to be pitted against one another. It is the policies and objectives which they are used to advance that need to be seriously studied. They determine the proper position and stand that should to be taken. In the HIBF, the people we invite annually as well as the guest country, (despite the variance in languages), pool their ideas and activities towards the lofty aim of our peoples' total emancipation, in which art, literature and culture play a most significant role. This is why we attach vital importance to our collaborations with African sister organizations.

Still on the subject of languages, how do you integrate the Somali language segment of the Hargeysa International Book Fair and the English speaking segments into a coherent whole?

So far the languages used in the HIBF are Somali and English. We haven't encountered any problems in this matter since almost all our guests are versed in English and the majority of our Somali audience (particularly the youth to whom we give special consideration) understand English fairly well. Our guest country for this year is Egypt. Understandably our dear guests will be speaking in Arabic. Here too we do not expect any problem arising since the vast majority of the audience know Arabic as their second language. In short, we have not as yet been hampered with the issue of interpretation and translation.

Africa is currently occupying centre stage in industry discussions around the imperative to translate texts across borders.

Talk a little about the publishing and translation work you do at Ponte Invisible which is the publishing arm of the Hargeysa Cultural Centre.

Broadly speaking translation plays an essential part in bringing peoples far apart in our world closer together. Through translation we come to know other peoples' arts and culture, their histories, traditions, likes and dislikes, ways of life, aesthetics. Furthermore, we get to know similarities we share. This knowledge of the other makes us more familiar with them, dispelling at the same time a lot of wrongly conceived beliefs we might previously have harboured. As a consequence, this enlightenment instils the commendable attitude of tolerance and makes living together much easier and our lives more enjoyable.

For all these important values afforded by translations, we embarked on the works of translation early on. But our scale is limited owing to our meagre means.

So far we have translated into Somali and published bilingually, literary works of prominent world writers such as Anton Chekhov's "Selected Short Stories", George Orwell's Animal Farm, Charles Dickens' The Signalman, Edith Nesbit's The Marble Finger, Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant and The Happy Prince, Robert Louis Stevenson's The Body Snatcher and others into Somali. Likewise we translated into English and published the poems of Mohamed Hashi Dhama "Gaarriye" (Gaarriye: Biography And Poems) and Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame "Hadraawi" (The Poet And The Man), just to name two of the most popular contemporary Somali poets.

Over the past ten years, we have maintained a close working relationship with the UK Poetry Translation Centre.

I have heard you reference criteria you use to guide your rights trading in translations. They are: Who is the knowledge producer? Who is the translator? Who is the publisher?

Shed light on these criteria and how they guide your translations.

Poetry is hard to translate. A process that worked for us for the translation of Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame's "Hadrawi", [known as "Somali Shakespeare" because of his influence], involves a double process of translation. A Somali scholar with a group of English literary people explains the poem during a dedicated workshop. From the workshop, they produce a prose-like literal translation of the piece. The essay produced is then given to an English mother-tongue poet who writes an English poem on the concept of the Somali poet. A fine-tuned and final version is then undertaken by the English-speaking translator poet and the Somali poet. What we end up with is an English poem structurally, with concepts and philosophy poetically expressed in Somali. It is such a powerful experience.

Let me quote something you wrote in your excellent article in Africa & Mediterraneo (Issue No 89, Vol. 2/18)

" ...in the Hargeysa Book Fair as well as in the activities we practise in the Hargeysa Cultural Centre, our aim is far from commercialisation. We are simultaneously building the environment to generate, promote and share knowledge with a society that is not always ready to receive or embrace art in all its diversity"

What kinds of interventions have you introduced to help make your people more receptive to diversity?

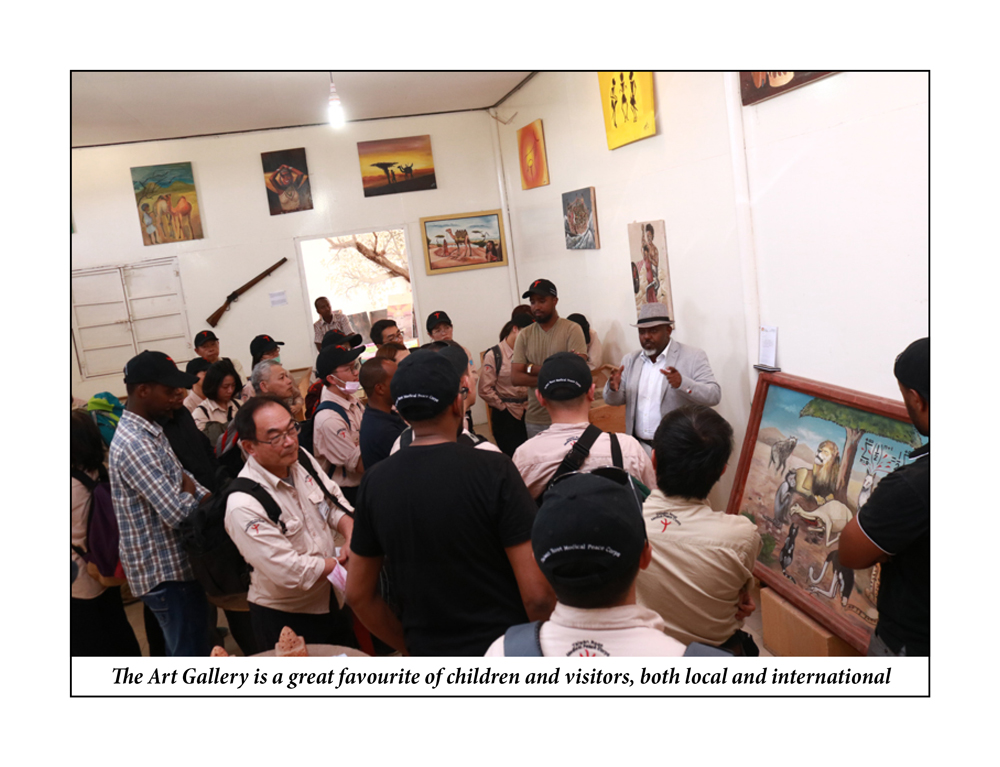

Since the inception of the Cultural Centre, we have been building and expanding constantly to accommodate our growing activities and demand for different spaces for different art forms. Painting, for instance, was not historically part of artistic expression of the Somali people. Today however, we have talented young self-taught painters who, despite the total absence of schools of art, are producing impressive art works. We yearly organize courses in creative photography and creative writing, acting and film script writing. And other similar literary activities. Many young people have found a safe space and a home with us, where they can create art and produce knowledge. As in many other African countries, the talent is here; it just needs an enabling environment to unlock. That is what is happening right now in Somaliland.

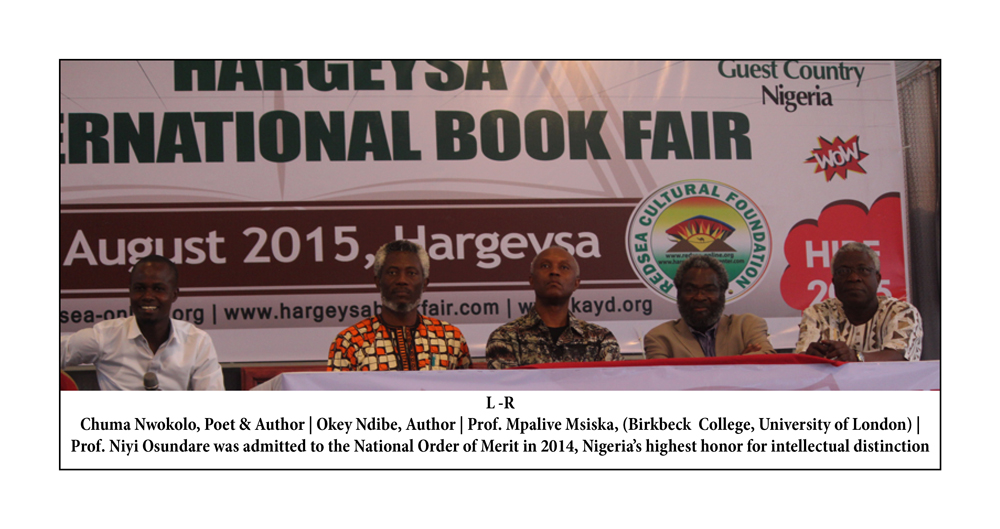

My country, Nigeria, has been a Guest of Honour of the HIBF. I feel very proud.

Please give some feedback from the Nigerian experience.

Nigeria was among the first countries to be invited as a guest country to the HIBF. Why? Because Nigeria is spectacular in many ways:

It is the most populous African country, occupying a vast geographical area, rich in both natural and mineral resources, multi-cultural in its social structure, and possessing some of Africa's most ancient cultural heritages. But beyond all these noteworthy factors, and for the sake of our commonalities in the field of arts and culture, Nigeria is teeming with distinguished scholars, poets, artists, publishers, intellectuals, journalists, thinkers and writers in every walk of life.

Thank you so much Jama! I am so glad to hear Nigeria is enjoying this kind of reputation in the Horn of Africa!

We were so honoured to have such amazing and distinguished guests including Professor Niyi Osundare, Okey Ndibe and Chuma Nwokolo. There was a great deal to exchange, share and learn from each other. We truly benefitted from the expertise of these renowned men of letters. They also enjoyed their time in Somaliland. They discovered many similarities including our taste for goat meat and our preference for colourful clothes! In our Nigerian guests, we have wonderful friends and ambassadors for HIBF. Professor and poet Osundare composed several poems which have been published about his experience, including "The Leader and the Led", "History Lives Here" and the "Watermelon of Hargeysa". Chuma Nwokolo who holds the record for the most returning guest of HIBF, composed a moving piece of poetry, "The children of Laas Geel". Our publishing arm, Ponte Invisible, also published Chuma's novel "The Extinction of Menai".

Give us examples of themes you have adopted for HIBF in the past; tell us what the theme is for 2019 and about how you use themes at HIBF.

Right from the outset of launching the HIBF in 2008, we adopted the policy of choosing themes central to the interventions made in all the sessions while the Fair is in progress.

These themes are carefully chosen from lofty principles and concepts cherished by humanity everywhere for their benefits. They are to be highlighted by all the participants in their own specific area of contribution in the Fair's programme. Later on when the guests return to their respective countries, these themes are further disseminated to their readers, followers and the general public in their countries.

We started in 2008 with Freedom followed by Censorship, Citizenship, Collective Memory, Visualization of the Future, Journey, Imagination, Spaces, Leadership & Creativity, Connectivity and Wisdom. This year's theme is Co-existence. We will focus on the principle of peaceful co-existence of nations and peoples in its broader sense beyond the narrow political plane.

While you were living in Italy and observing the political turmoil in your country, you and your compatriots over there felt the urgency to help oversee the transition of Somaliland from an oral culture to a written culture.

What aspects of the political turmoil and its outcomes provoked that sense of urgency to see a written culture take root in your country?

I was one of the fortunate people who living in Italy had both the time and privilege to become conversant with the world around me and the drastic changes brought about by the dynamic development of science and technology. Following the collapse of the Somali Republic in 1991 and having declared independence, Somaliland was trying to construct both its institutions and a broken society with no external help or finance. Art, culture and books, were certainly not a priority, and to most seemed even a little crazy, but we strongly believed that in the short term, arts and culture could help with the recovery and healing of our society and in the long term be truly instrumental in the cultural transformation of the semi-literate Somali society.

We wanted to stimulate the revival of all forms of art and human expression, including painting, poetry, story-telling, theatre and music, but most importantly we wanted to create a platform where authors and other artists meet their readers and the general audience. To that end, our core aim was to promote a reading and writing culture, tolerance, freedom of expression, democratic values and inter-generational discussion through literature and discussions. As such our activities, besides the exhibition of books which is an integral part of the programme, continued to grow on a yearly basis. Now they embrace a wide range from poetry recitation, painting, panel discussions of crucial issues, documentary film screening, music and theatrical performances. We also provide short intensive training on creative writing, photography, film-making and dancing plus many others.

Let me quote/paraphrase a statement you made at the Lettres d'Afrique at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2018: "If arts and culture were promoted by government, it would infuse humanity into nation-building and it would help to limit extremism in the Horn of Africa."

What is the connection in your view between arts in nation-building and the reduction of extremism

Extremism is one of the most loathsome and dangerous attitudes and passions to take hold of a human being. A quick survey of our world just over the past three decades would clearly reveal that nothing could match, in scale and intensity, the hell and havoc caused by terrorist acts in many countries across the globe. These terrible atrocities most unfortunately, continue to this day to be committed by individuals, groups or organizations driven by either political or religious extremism.

Throughout history, art has always played an essential role in the service of human progress. What is well-recorded in history are the huge sacrifices made by artists in their quest to improve the quality of human life by inspiring freedom, justice, tolerance, equality and human dignity. On the other hand, extremist forces of darkness and reaction in society whether in power or in the opposition, have been the sworn enemy of enlightenment and human progress. One can safely say that art and extremism are anathema to each other: the growth of one signals the death of the other.

This is the perspective that guides all our activities in the Hargeysa International Book Fair and the Hargeysa Cultural Centre. The central themes we keep adopting annually for the Book Fair and the guests we invite are proof of our staunch alignment to the forces of hope and live.

Finally, you are particularly passionate about not only the need for Africans to produce knowledge but for that knowledge to move around the world. You have complained about the fact that a book published in Nairobi is not available in Kigali. You find it totally unacceptable that a book you can buy in Hargeysa from London within 48 hours cannot be bought from Nairobi which is a mere hour's flight from Somaliland.

What are the bottle-necks to cross- border trading? And what can be done about them?

The simple answer is to demolish these barriers; but the policies to be followed and the practical measures to be taken for the fulfilment of this objective is not as simple as it sounds.

The era in which we live has its own characteristics: globalization and all its entanglements. Regional integration, making the best use of the dynamism of science and technological changes, becomes an imperative facing the developing world including African countries.

The recent call for the regional integration of countries in the Horn of Africa, spearheaded by Ethiopia, is the latest example to cite. All the bottlenecks one can think of are present in this enterprise both locally and internationally, but they must to be faced courageously and sagaciously.

All habits, traditional values, parochial relations, devout adherence to ethnicity, are some of the bottlenecks met with locally. This is further militated by international intervention with its powerful potentialities coupled with heinous machinations.

Confronting these forces of reaction is never an easy task. It requires first and foremost a common and clear political vision to be adhered to and followed by the implementation of economic, social and trade relations among African nations.

Despite these difficulties, all necessary measures for regional integrations in all spheres must be carried out with unflinching determination. The cooperation and collaboration of all those involved in the field of literature, artistic activities, book publication and knowledge production, on a regular bases, must be put into real practice.

I am drawn to people of mixed-cultural descent and of mixed-race heritage. I'm also drawn to ...

David Aguilar, born in Andorra, is an inspiring figure known for his resilience and crea ...