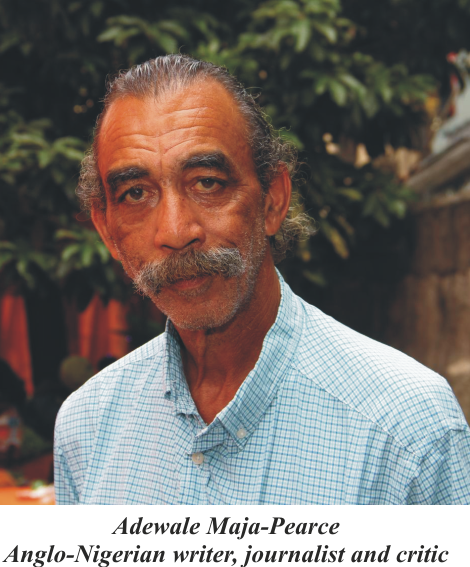

You are the co-founder of The New Gong which your

website describes as ‘publishers of new writing and images’ and, intriguingly,

as ‘an experiment on how writers could

be useful to each other beyond drinking together’.

You are the co-founder of The New Gong which your

website describes as ‘publishers of new writing and images’ and, intriguingly,

as ‘an experiment on how writers could

be useful to each other beyond drinking together’.

What about the vision driving The New Gong? In particular the vision behind the collective approach, what you describe as ‘writers [being] useful to each other’.

What is the significance of the name?

The New Gong was Dulue’s idea. It evokes the village gong, town crier, that kind of thing.

12 years on, how has this “experiment†played out in practice, and what have been the main challenges?

The lack of distribution networks in Nigeria has been a major obstacle. There is no chain bookstore in the country like Borders in the US or WH Smith in the UK which will stock your books nationwide once you send the required number of books to their main centre. The infrastructure here – as in so much else – is poorly (or not even) developed.

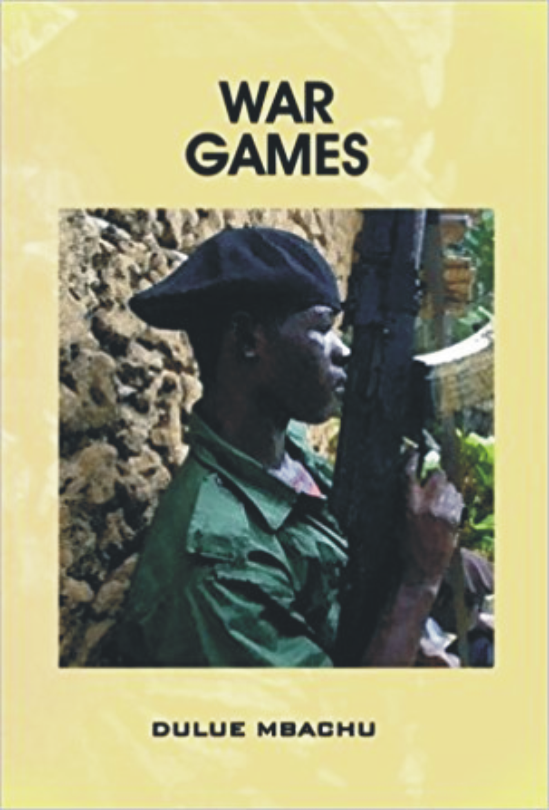

What prompted the publication of The New Gong's Issues in Contemporary Nigerian Art by Juliet Ezenwa Maja-Pearce? And how - being an expensive enterprise to publish art books - was it made possible?

My

wife, Juliet, who is a visual artist, simply asked The New Gong to publish her

book! From that experience we have evolved into a specialist publishing house

receptive to people with interesting ideas. The publication was made possible

with funding from the Ford Foundation which Innocent Chukwuma leads. I have

known Innocent since his days at the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO). He

liked the idea of the book. Ford provided support for printing in the UK,

distribution, marketing to university art departments and the launch. It was

held here in the garden.

My

wife, Juliet, who is a visual artist, simply asked The New Gong to publish her

book! From that experience we have evolved into a specialist publishing house

receptive to people with interesting ideas. The publication was made possible

with funding from the Ford Foundation which Innocent Chukwuma leads. I have

known Innocent since his days at the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO). He

liked the idea of the book. Ford provided support for printing in the UK,

distribution, marketing to university art departments and the launch. It was

held here in the garden.

In his history of art book, New Trees in an Old Forest, Jess Castellote laments the lack of a corpus of art criticism in Nigeria to properly respond to the exploding production of visual art. What has been the reception to your book Issues in Contemporary Art, so far?

It has not been reviewed at all. Not even by academics at the various universities which have copies. We don’t have a reviewing culture in Nigeria. It is my pet peeve. We don’t have a culture of art or literary journalism. In the UK, there is very high level reviewing, not academic criticism, just plain reviewing, widely available. Journalism is in a crisis in this country.

And how challenging has it been to market a publication of this nature to a worldwide audience?

Having served as a member of the jury for the once prestigious but now discontinued Noma Award for Publishing in Africa, I thought you would be well-positioned to comment on the evaluation processes employed by Nigeria Liquefied Natural Gas Ltd (NLNG) for the Nigeria Prize for Literature.

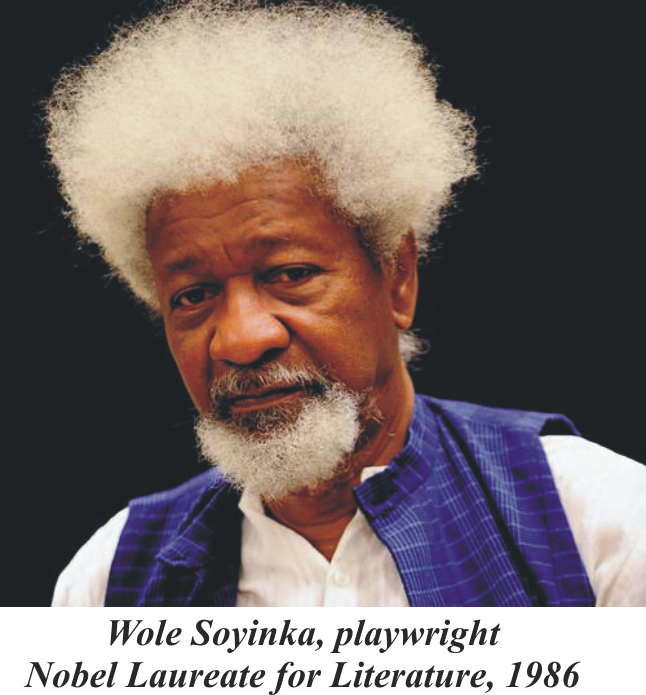

Your quarrel with the Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka, has been richly documented online. You have also generously provided a record of the rancour between you and the contributions of others to it, on The New Gong website under the title, ''My Original Sin Against Soyinkaâ€. http://www.thenewgong.com/originalsin.html

Tell us a little of the genesis and escalations of this ‘battle’ and how you believe publicizing it, to paraphrase your words, contributes value to Nigerian literature.

I’d written a review of his memoir, You Must Set Forth at Dawn. I didn’t like it and said so. I thought it was sloppily written. It was all over the shop. All celebrating Wole Soyinka. The value of writing a memoir is that you are an actor in a wider drama. It ought to have given us insight into the drama of Nigeria. It shouldn’t be celebrating you as a person.

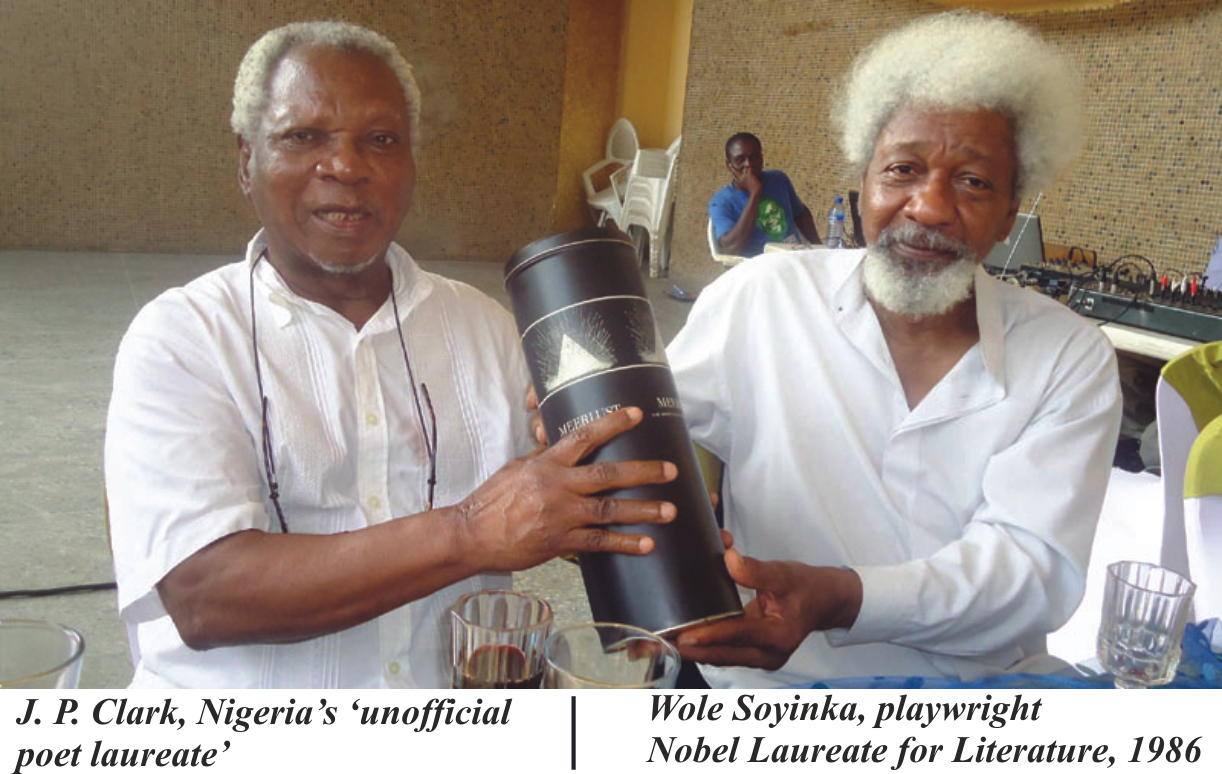

The first missile I got was when I ran into a problem with the poet, JP Clark, whose biography I was writing at the time. I didn’t know Soyinka was seething over my review in the London Review of Books (https://www.lrb.co.uk/v29/n15/adewale-maja-pearce/our-credulous-grammarian).

I wrote to him to ask him to share his thoughts on

his highly publicised fight with JP. I wanted clarifications about a remark he had

made in The Man Died, his prison memoir, regarding JP spreading a rumour

about his health at the time of his imprisonment, largely in solitary

confinement. There was concern at the time that the military government wanted

to get rid of Soyinka and Soyinka accused JP of going around the world claiming

that he – Soyinka – was suffering from syphilis. But all I got in return was this abusive

email. It took me by surprise. He was a lot

more concerned about the review than about the whole JP syphilis saga. From

then on I got a lot of abuse from him. At JP’s 80th birthday

celebration at University of Lagos, in his keynote speech, he accused me of

being a jumped-up non-writer, etc.

I wrote to him to ask him to share his thoughts on

his highly publicised fight with JP. I wanted clarifications about a remark he had

made in The Man Died, his prison memoir, regarding JP spreading a rumour

about his health at the time of his imprisonment, largely in solitary

confinement. There was concern at the time that the military government wanted

to get rid of Soyinka and Soyinka accused JP of going around the world claiming

that he – Soyinka – was suffering from syphilis. But all I got in return was this abusive

email. It took me by surprise. He was a lot

more concerned about the review than about the whole JP syphilis saga. From

then on I got a lot of abuse from him. At JP’s 80th birthday

celebration at University of Lagos, in his keynote speech, he accused me of

being a jumped-up non-writer, etc.

What did you think of Dreams from my Father by Barack Obama?

Why did you go public with Wole Soyinka’s rancour against you on The New Gong website?

If you wrote a biography of JP Clark, your opinion of him must be very high.

One of those who weighed into your clash with Soyinka

was the writer Ike Oguine. In his letter, he veers off the subject,

though, to address what he views as deficiencies in the content and style of

your criticism of Soyinka's play, The Road.

letter, he veers off the subject,

though, to address what he views as deficiencies in the content and style of

your criticism of Soyinka's play, The Road.

Would you be ready to re-consider your critique of The Road in the light of Oguine's thoughts?

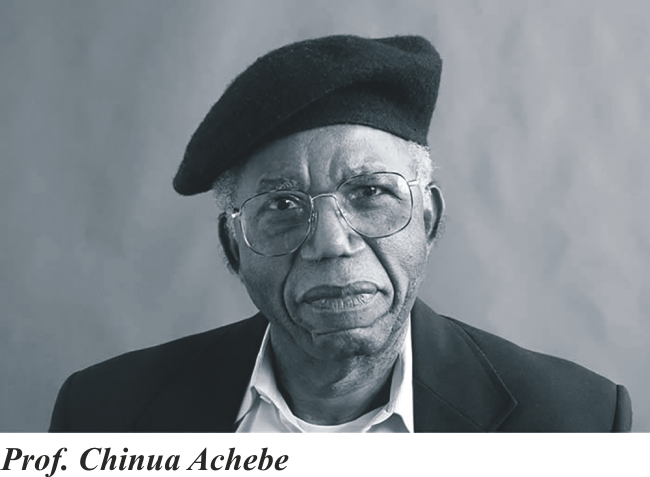

Not at all. It was in the context of the whole language issue. This is, to me, a matter of great mystery. One of the chapters in my JP book is dedicated to not just The Road, not just to Soyinka, though he’s a good example of the thing I want to talk about. Soyinka is a playwright of the Yoruba nation. Yoruba land has a long and distinguished tradition of drama. It is the main Yoruba literary vehicle. Moreover, at the turn of the last century there was great consciousness on the part of Yoruba intellectuals to revisit their culture which, due to colonialism, was under attack. By the early 1940s, this led to a revival of Yoruba drama with Hubert Ogunde at its helm. He and his troupe performed dramas across Yoruba land which the people could hear and understand. A Nigerian political leader banned Herbert Ogunde’s plays but never banned Wole Soyinka’s. But how do you communicate with Yoruba people in English? Soyinka’s The Road isn’t comprehensible to a Yoruba audience! Tolstoy wrote in Russian. Write in your language and in your own cultural idiom. Soyinka is actually writing English literature for a global English-language audience. The title of that chapter was ‘What is Wrong With Writing In Your Own Language?’ I went to every interview Soyinka has ever given and this question crops up again and again. And he can never give a straight answer. He says he doesn’t want to speak only to the Yorubas. In fact he has betrayed his culture, just as Chinua Achebe has also done.

The problem is that this Yoruba language, this Igbo language, will die if people don’t write in it.

From time to time, I hear similar views aired about

your approach to literary criticism, which some might say is deliberately

provocative. Would you care to respond

From time to time, I hear similar views aired about

your approach to literary criticism, which some might say is deliberately

provocative. Would you care to respond

You were the Series Editor for the famous African Writers Series (AWS) published by Heinemann.

Can you go back in time and talk to us about your experience while you served in that capacity.

I was brought on board as a consultant by Vicky Unwin, the publisher. We could only publish six titles a year. The series itself was initially sustained by the burgeoning need for books in Nigerian universities. But once IBB came in and the IMF introduced the Structural Adjustment Program in the mid-1980s everything changed. Things Fall Apart was like the American economy before the Chinese came, but other than that scale was not enormous at AWS. Things Fall Apart by itself sustained the series. It was a calling card. Everyone had read it. The second money spinner was another Achebe title, No Longer At Ease! I made some innovations: introduced poetry, and Vicky allowed me a few anthologies and I sneaked in some stand-alones. The readers of our manuscripts were European Africanists, by the way, not Africans. AWS was based in Oxford. Publishing African books in Oxford is paradoxical, a contradiction somehow.

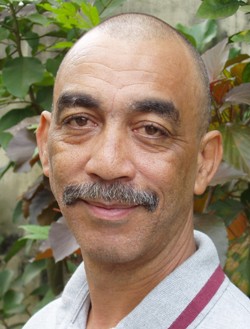

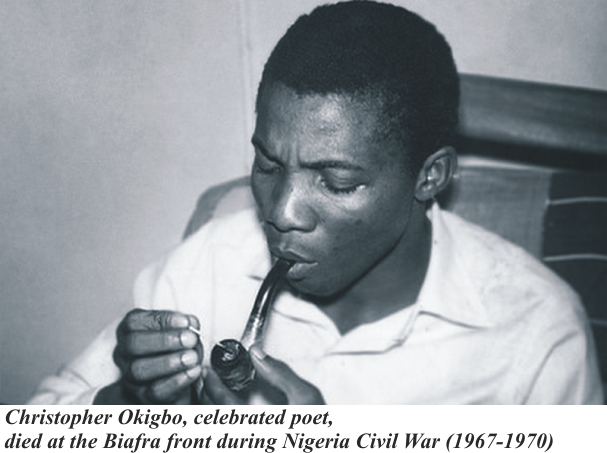

Of your books, the one I know the best is The House My Father Built published by Farafina Books. You are, however, recognised locally and internationally for several more, and now I'm quoting, “illustrious work(s)†ranging from your volume of Christopher Okigbo's Collected Poems (1986) to your travel essay, In My Father's Country (1987).

In My Father’s Country was the first part of a trilogy. The House My

Father built was the second. I jokingly tell people that the third

one, which I haven’t written yet, will be ‘A Farewell to My Father’s

Country’!

In My Father’s Country was the first part of a trilogy. The House My

Father built was the second. I jokingly tell people that the third

one, which I haven’t written yet, will be ‘A Farewell to My Father’s

Country’!  I

left Nigeria when I was sixteen for the UK. I came back twenty years

later. When I left, my notion of Nigeria

was limited to Obalende, where I schooled, and Ikoyi, where we lived. It was my boarding school memories which

brought me back. I was happy there. It was my first time out of the colonial

bubble of Ikoyi with its St Saviour’s and Corona Schools, where we even had

teachers from England. I learnt to speak Pidgin (so-called) and made good

friends, some of whom I retained. While I was living in England, I wrote short

stories called Loyalties based on my memories of Nigeria.

I

left Nigeria when I was sixteen for the UK. I came back twenty years

later. When I left, my notion of Nigeria

was limited to Obalende, where I schooled, and Ikoyi, where we lived. It was my boarding school memories which

brought me back. I was happy there. It was my first time out of the colonial

bubble of Ikoyi with its St Saviour’s and Corona Schools, where we even had

teachers from England. I learnt to speak Pidgin (so-called) and made good

friends, some of whom I retained. While I was living in England, I wrote short

stories called Loyalties based on my memories of Nigeria.

The House My Father Built has been very well received. Congratulations, Adewale. And thank you for coming on Borders. Click Here to get a copy

I am drawn to people of mixed-cultural descent and of mixed-race heritage. I'm also drawn to ...

David Aguilar, born in Andorra, is an inspiring figure known for his resilience and crea ...